Why Should We Care About Literary Awards and Winners?

Following the Paris Review’s announcement of Richard Ford as the 2020 Hadada award recipient, authors and readers were quick to underscore a well-known, historical bias regarding some of the biggest national, literary awards—cisgender, white men mostly win them. Oh, and Richard Ford once spat on Colson Whitehead after Whitehead gave a negative review of Ford’s short-story collection, A Multitude of Sins. Let’s not gloss over that detail.

I started looking at some of the figures myself when Paisley Rekdal, two-time Kingsley Tufts Award finalist, highlighted the demographics of previous Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award winners for both fiction and poetry in an illuminating thread on Twitter. Spoiler alert: the numbers confirm the bias—surprise, surprise. (At this point, dear reader, if you find yourself saying something like “but what if all those white men did write the best books” or anything along those lines then you should probably stop reading this and read Richard Ford. . . ?)

1. This is going to be long.

I've never heard of this award, but I was astonished to see the list of winners, and the list of writers absent from this list. And it got me curious, so I went to do a quick search of some of our biggest national awards, to see who was winning what. https://t.co/sttQCDEAPL

— Paisley Rekdal (@PaisleyRekdal) November 5, 2019

These conversations about inequality in publishing and awards decisions are not highlighting anything new, and the criticism needs to continue until things change—the numbers are skewed despite the fact that for every good book written by a cisgender, white man, there is a good book written by a non-cisgender and/or non-white and/or woman, so how will selection committees and organizations make changes to their systems to better reflect what is published?

In light of all this, I was particularly interested in the attitude of some who were (or are) more or less critical because they say “awards don’t matter.”

Sure, “awards don’t matter” when considering the motivation for writing, the enjoyment of reading, and the discourse on literature, sensibility, and individual taste writ large. Numerous factors that determine what make this book “better” than that book are mostly subjective and arbitrary. I also fully understand and often support the impetus of an “awards don’t matter” attitude when taking a stance against an elitist, tyrannical posture of any institution or organization that claims to be the superior authority on what is “good” or “bad” in art or literature.

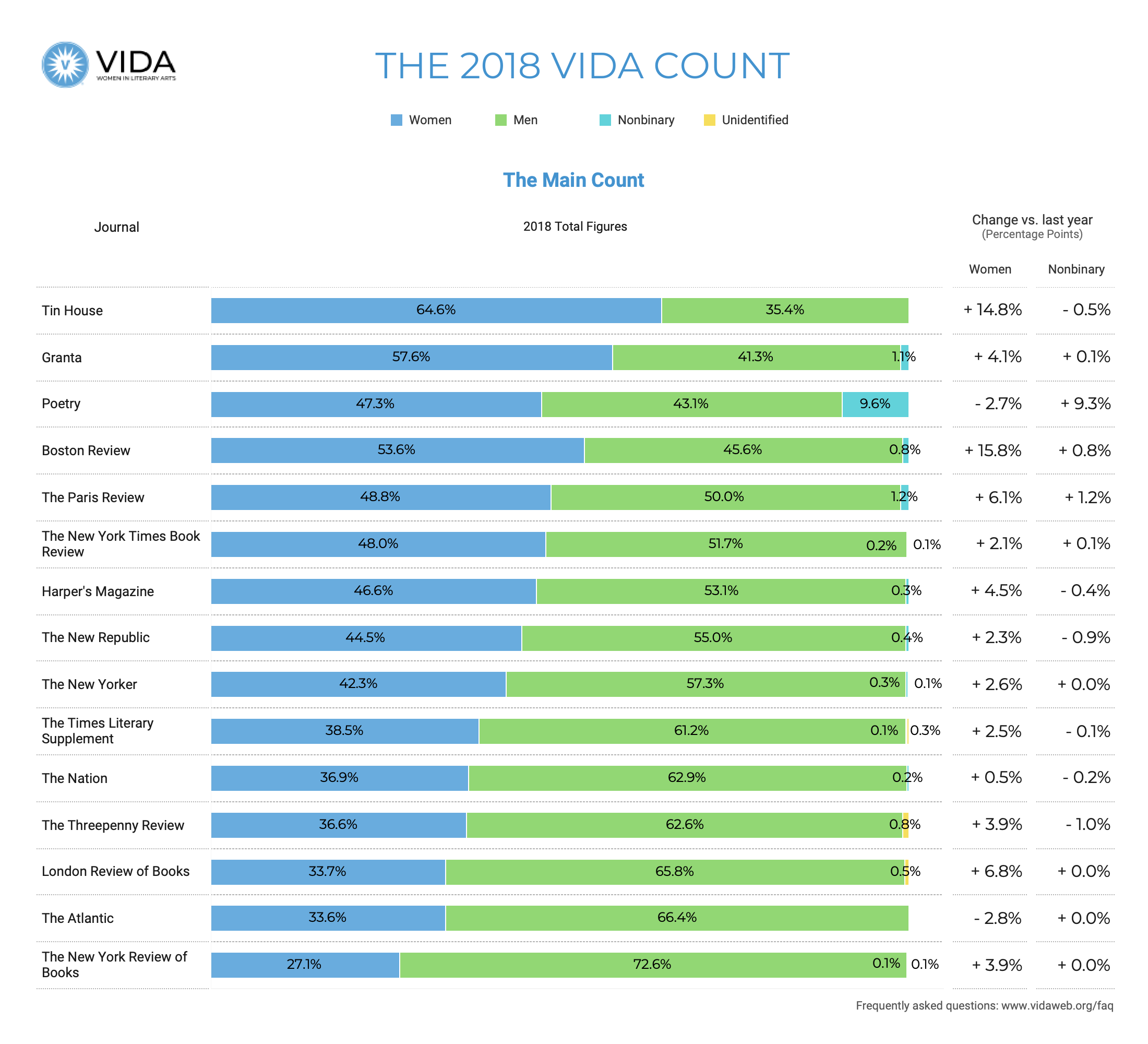

Yet I think the point of having literary awards, quite simply, is to recognize and celebrate exemplary literature by spotlighting and commemorating some of the contemporary moment’s great works and the efforts of such creation. And to be a finalist or on a short or long list for awards is a way to say to the public, “Look at all of these talented authors and gorgeous books! Read them!” And more often than not, this visibility is a conduit for finding out about other related works and authors in a particular genre. (We here at the Tufts Awards did our own VIDA count a few years ago.)

So the parity of it all matters. These discussions matter. Ultimately, who will be recognized and who will not? Who will continue to reap benefits and who will not? The point is this: literary awards systems are not perfect but actions can be taken to ensure that nominees, finalists, and winners represent the expansiveness of the literary world. Through monetary prizes, recognition, and/or other accolades, awards afford privilege to writers and their communities, so it matters who is receiving these awards and why.

p.s. The work of an organization like VIDA: Women in Literary Arts is particularly poignant and relevant to this conversation. See what they do here.

p.p.s. Oh, and sorry for all this talk about fiction writers. I’ll be back with regularly scheduled poetry programming in my next post.

—Stacey Park

Share