Why we count

In one of my freshman composition classes last year, I had my students name every single author that they could think of and wrote them on the board. The majority of them were white men. Women were grossly underrepresented. Women of color had a count of two. A few years ago, I asked a smart friend of mine with a bachelor’s degree if he could name 10 women authors. He couldn’t.

VIDA Women in Literary Arts is a non-profit organization that does a much more scientific study of these disparities. It breaks down the gender distribution of published and interviewed contributors in several literary journals like the Atlantic, the Boston Review, the New Yorker, and Harvard Review. When their count began in 2009, it was simply a matter of distinguishing women versus men, but recently VIDA has expanded their count across the spectrum to include authors that identify as trans, genderqueer, asexual, and more.

VIDA’s initial count included a total for 2009 and a historical count. The historical count measured The American Book Awards from 1980 through 2009. Men far outweighed women, with the latter representing a mere 33 percent. 2009’s figure, which looked at both publications and awards, showed an almost identical distribution. The 2015 VIDA report revealed that overall, women still made up about one-third of the publishing pie.

In her introduction to the 2015 report, VIDA chair Amy King asks, “If certain women’s voices are absent or poorly represented in mainstream publications, how does that deficit shape public thought?”

One answer is a student in my composition class (in earnest) suggesting that perhaps men are simply better at writing; another is the inability of an intelligent person to identify just ten of the plethora of women who have contributed great writing to literary history. The disparity in the publishing world trickles into our collective consciousness.

Though these numbers seem disheartening, there are publications that are closer to equality. In 2015 the Paris Review reached gender parity with women representing 51 percent of published work. Poetry had a 49 percent representation and transfeminine and genderqueer/gender fluid combined came in at .08 percent.

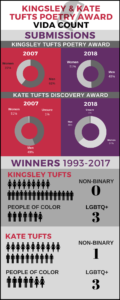

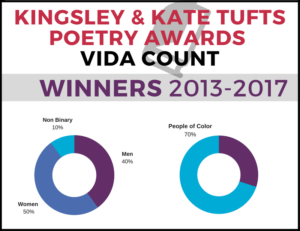

Curious about the way that CGU’s Tufts Awards has or does represent women, people of color, and varied genders and sexualities, I took it upon myself to do a mini count of the awards’ submissions and winners. The list of winners is tilted egregiously towards white male cis-gendered poets, with only one woman of color ever winning the Kingsley Tufts Award (this year’s winner, Vievee Francis); but submissions show more optimistic numbers. Submissions for the Kate Tufts Discovery Award was near equal distribution in 2007, and female authors for the 2018 Kate Tufts represented 64 percent of submissions. 2018 Kingsley Tufts submissions totaled an almost exact 50 percent.

Obviously, gender disparity happens on a variety of levels, and VIDA’s count measures just one tendril of the Medusa through which sexism functions. Is it possible that more women submit to the Kate Award because it is named after a woman? Certainly. Is it possible that the Kate Award, given for a first book of poetry, receives more submissions from women because many first books are published from contests, where manuscripts are blind read? Of course.

Our Tufts Awards count, too, is neither comprehensive nor without prejudice. We counted only submitters’ genders based on first names and/or a Google search. With our winners we could be a little more specific. This infographic reflects our findings.

The upside: Over the past five years, the distribution of our winners reflects much more diversity.

Another question King asks, rhetorically, is “If the literary landscape is dominated by specific groups, how can we be healthy as a society and benefit from both our differences and commonalities?”

We can’t. Here at Claremont Graduate University’s Kingsley and Kate Tufts Poetry Awards, and in the broader poetry landscape, we hope to see as much heterogeneity as possible.

—Emily Schuck

Share