On Writing Practices and the Academic Calendar

Many poets—both aspiring and established—find themselves tied to an academic calendar. While this calendar provides consistent (and occasionally cathartic) semester breaks, the crazed weeks during the semester can bear a crushing weight on anyone’s creative pursuits. As we head back into another academic year, we face a familiar question: how do we balance creative and academic work?

This post is a round-up of writing advice from poets and writers who have something to say about developing a writing practice. Specifically, we’re interested in how these tips might apply to maintaining a creative and academic balance. While the lines between creative work and academic work are often fuzzy, there’s still no reason you have to put your personal writing on hold for the next four months. For a more balanced semester, see the tips below, along with the writers who champion them:

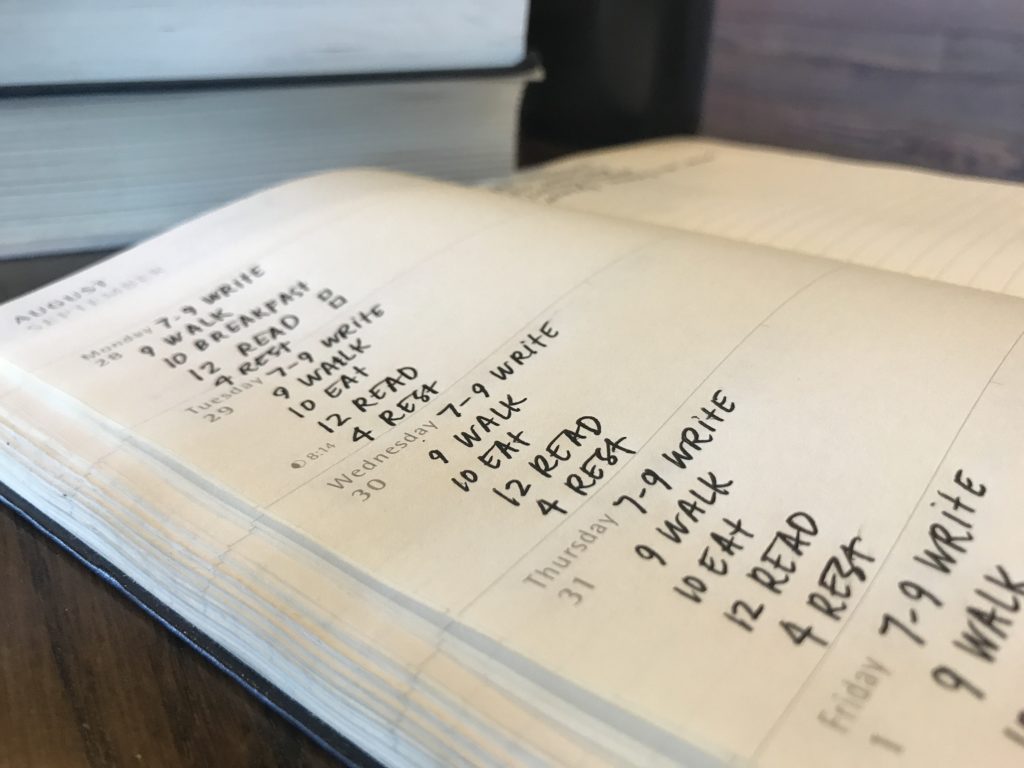

1. Build a schedule. It’s the most obvious writing advice you’ll ever get, but that doesn’t make it any easier. In his 2013 book—Daily Rituals: How Artists Work—writer and editor Mason Currey examined the creative rituals (including schedules) of over 150 creatives. Though he found that many creatives work/ed best in the early morning (e.g. Sylvia Plath, Toni Morrison, Haruki Murakami), others are/were drawn to the late hours of the night (e.g. Franz Kafka, Marcel Proust). No matter when and how you write, setting a schedule is essential to your practice.

2. Protect your time and space. Boundaries are important for both the creative and the academic. Once you have built a schedule for your time, treat it like how you would treat your most important obligation. One blogger/writer, James Clear, has taken a particular interest in the habits of successful creatives, and he offers sound advice for aspiring writers: “Professionals stick to the schedule, amateurs let life get in the way. Professionals know what is important to them and work towards it with purpose, amateurs get pulled off course by the urgencies of life.”

3. Minimize distractions. Along with protecting time and space, it’s important to protect your focus. There are any number of ways to create this focus, but Don DeLillo‘s method is especially creative:

“A writer takes earnest measures to secure his solitude and then finds endless ways to squander it. Looking out the window, reading random entries in the dictionary. To break the spell I look at a photograph of Borges, a great picture sent to me by the Irish writer Colm Tóín. The face of Borges against a dark background—Borges fierce, blind, his nostrils gaping, his skin stretched taut, his mouth amazingly vivid; his mouth looks painted; he’s like a shaman painted for visions, and the whole face has a kind of steely rapture. I’ve read Borges of course, although not nearly all of it, and I don’t know anything about the way he worked—but the photograph shows us a writer who did not waste time at the window or anywhere else. So I’ve tried to make him my guide out of lethargy and drift, into the otherworld of magic, art, and divination.”

4. Show up, be consistent. Mary Oliver‘s thoughts on writing emphasize the significance of bringing one’s whole self to the page when writing.

“The part of the psyche that works in concert with consciousness and supplies a necessary part of the poem—the heart of the star as opposed to the shape of a star, let us say—exists in a mysterious, unmapped zone: not unconscious, not subconscious, but cautious. It learns quickly what sort of courtship it is going to be. Say you promise to be at your desk in the evenings, from seven to nine. It waits, it watches. If you are reliably there, it begins to show itself — soon it begins to arrive when you do. But if you are only there sometimes and are frequently late or inattentive, it will appear fleetingly, or it will not appear at all.”

If, as Oliver says, the creative mind depends on this consistency, your craft will improve as you show up.

5. Finally, don’t forget to maintain a life. Contemporary poet Sarah Kay encourages writers to get out and engage with the world in order to generate creativity: “When something penetrates your thoughts and feelings, jot down a one-word reminder or send yourself a text message. Later, when you carve out time to write, those words can move you toward writing ideas. It’s like breadcrumbs that head you toward inspiration.” For those prone to isolation in the thick of the semester, this advice is imperative to generate creativity and stay motivated.

—Ashley Call

Share