Thoughts on Brendan Som’s The Tribute Horse

By far, the best advice about reading poetry is: Memorize. But don’t immediately run screaming from that hated, school-bogged word; instead, consider that memorization is not always the result of a process of mechanical repetition. Sometimes, memorization is spontaneous, automatic—even involuntary. It only takes one listen for a snatch of particularly catchy music to get stuck in someone’s head. And so it is with poetry. The greatest moments of poetic achievement cause the lines of a poem to latch onto the imagination like a bur to clothes. This process of poetic take-out allows us to place lines of poetry in our everyday lives. Who, for example, when our latest president was sworn in, did not think: “And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,/ Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?”?

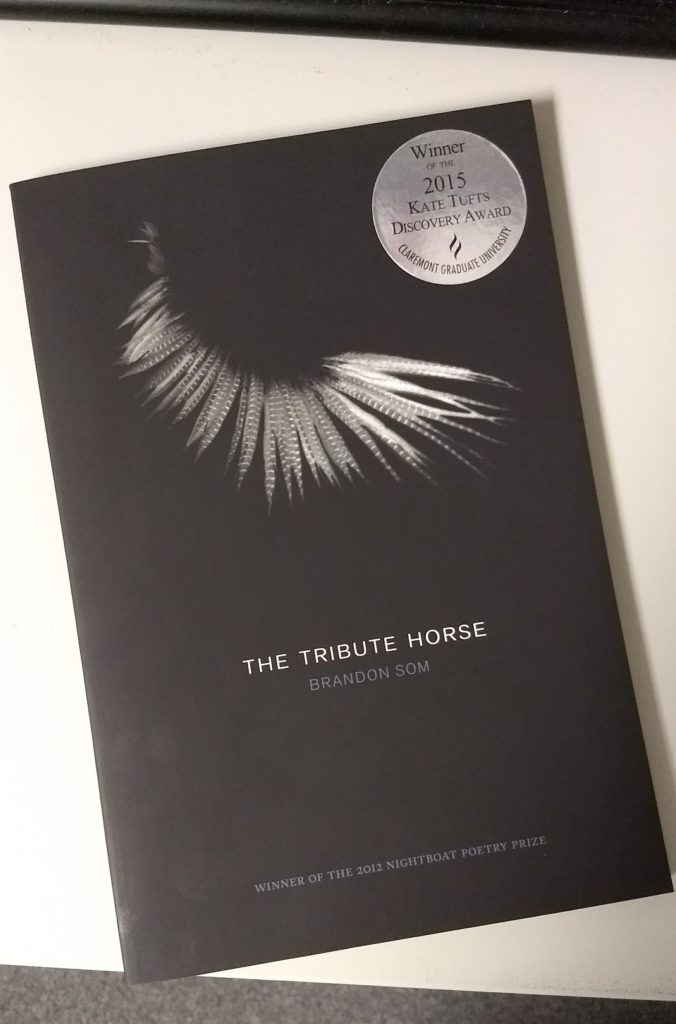

And that seems to be the organizing principle for Brendan Som’s The Tribute Horse, winner of the 2015 Kate Tufts Discovery Award for a first book of poems. It is impossible to miss the sonorous quality of Som’s lines. In John Yau’s review of Som, Yau puts it simply: “Som uses sound, rather than narrative, to access a little-known history of the illegal immigration of Chinese into America.” The Tribute Horse is riotously alliterative and full of assonance. In a line like this from “Seascapes”: “They say in certain shells/ you still hear the sea…” Yau’s observation becomes like fact. We can hear the hiss of the waves through the soft consonant repetition. Irresistibly, the poetic line stows away in the procedural memory—which is the part of our brains that remembers music no matter how old we become.

For more context, Som is clearly a scholar of poetry as much as he is an artist. His admitted reference to Modernist poet Ezra Pound’s work is abundantly clear. Pound, too, was fascinated by sound’s ability to recall physical phenomena—particularly the sound of waves. In an article titled “Hugues Salel” (1918), Pound writes: “Of Homer, two qualities remain untranslated: the magnificent onomatopoeia, as of the rush of the waves on the sea beach and their recession as in παρὰ θι̃να πολυφλοίσβοιο θαλάσσης [para thina poluphloisboio thalassês] untranslated and untranslatable…” Som seems deeply influenced by this sentiment, to say the least.

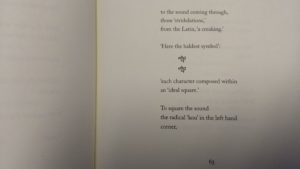

Not only does Som echo Homer’s lost sound of the sea, Som also borrows Pound’s famous language-swapping technique as well. The Cantos is inundated by phrases—sometimes entire poems—in multiple languages. The same is true for The Tribute Horse. Chinese characters as well as the phonetic pin-yin and words in Spanish, Latin and Italian litter poems like “Bows and Resonators” and “Confessions.” Between the borrowed and translated Chinese poetry and influence of Japanese art, Som’s “debt of sound” is also a debt to Pound. Though readers may find Som the more readable poet: he is somewhat more patient. Spliced into poems like “Cuttings” are instructions for the pronunciation of “cuchillo,” and “yeoman’s yoke” and “yucca.” These helpful notes give the reader a clue about how to read these poems—out loud—and more importantly, how these poems should be considered. To Pound’s Piano Sonata in B. Minor, Som writes the lullabies: gentler, more melodic, almost parentally involved in teaching us to read them.

The effect of Som’s expert technique here is mesmerizing. Consider the power of Som’s alliteration in “Bows and Resonators”: “…or the / undersized // fighter brought finally to fury / by the tickling // of a ‘pig’s whisker,…’” Who can resist conjuring the image of a tiny warrior, springing to her feet with fists raised, ready to pound on a pig who just happened to sniff her face while she slept? Can we stop ourselves from hearing the “f” sounds as the warrior splutters in rage? Here displayed is the true force of lyric poetry. Building repetition into the line teaches us to, as we read, unconsciously encode these patterns in our thoughts. And without meaning to, we see these lines spring to life like they were seeds planted in the imagination.

I am certainly not immune. Just today—as I looked back at my own life and my own choices—I thought, without meaning to, about: “There were so many birds. How boyish, how foolish, to follow just one” (from “Tilde”).

—Kelly Eisenbrand

Share