The Kate & Kingsley Tufts Winners and Black Girl Magic

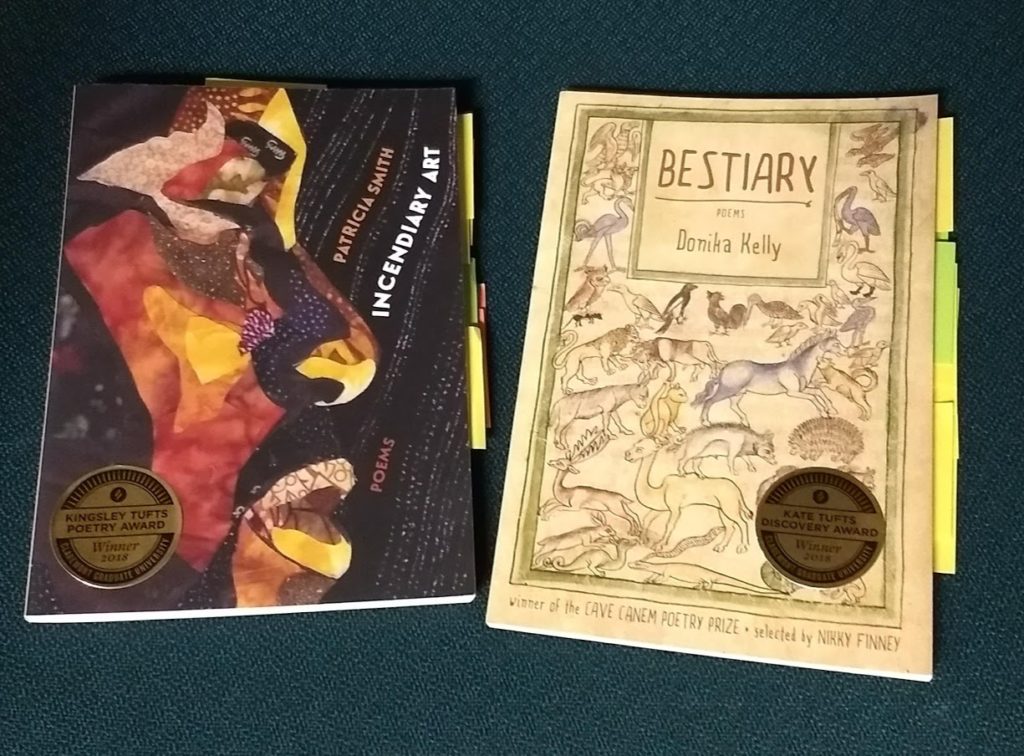

Donika Kelly and Patricia Smith are the winners of the Kate & Kingsley Tufts Poetry awards this year (respectively). The first striking similarity between these winners is their association with Cave Canem. Bestiary, by Donika Kelly, is the winner of the Cave Canem Poetry Prize, selected by Nikki Finney. Patricia Smith is a Cave Canem faculty member. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: the most important contemporary poetry right now is being written by extraordinary black poets, and Cave Canem is at the epicenter of the movement. But the bigger question, and the reason this observation is noteworthy, is significance of the thematic connectors through the work, and what those overlapping themes assert about how the readers and writers of poetry are responsible for changing the way we read, think, and live. The main overlapping theme seems to be that the poet is never separate: not from personal history, nor history as a whole. The present is merely what has been coming all along. Seeing the ugliness of the past and present doesn’t transform it into something beautiful, but nor does the clock stop. In other words, inventing the present is not a matter of transformation, but perspective.

In fact, it seems that the most productive way to view these works is as two different approaches to viewing history from a particular perspective. Kelly, for example, is heavily invested in reinventing classical mythology. In “Love Poem: Pegasus,” she writes “Foaled, fully grown from my mother’s neck, / her severed head, the silenced snakes…” (pg 18). Kelly narrativizes of the birth of Pegasus from the head of Medusa as a metaphor for love, and possibly parenthood, from the second person perspective. Second person is the most conversational and intimate perspective, as it is most commonly used in letter-writing. Thus, here, the broad and mythological serves as the functional metaphor for the most intimate and personal. Kelly is hardly the first writer to do this; Anne Carson has spent a large part of her career retooling Greek mythology for the purposes of fictionalization and poetic memoir. But the bestiary is in the tradition of the medieval practice, wherein documentarians recorded sightings of beasts both real and mythological and other natural phenomenon in order to draw moral lessons about the Word of God manifested in the physical world. If Kelly’s narrator is searching for the truth, she finds it in her own experiences and interpretations, not from any ancient tradition or religion.

If personal history is the site Kelly excavates to find the truth, Smith pulls out her search wider. Kelly’s perspective is as personal as it gets, interworked with the narrator’s own experiences, no matter how difficult. Included are testimonies like this one: “…The gusset of your panties soaked with your father’s semen. Why / you no longer wear panties. Why he / deserves every arc of your boot. Why / the door is always locked” (Bestiary, 33). Kelly takes no refuge in her poetic vehicles; her narrator is starkly vulnerable and available at no distance from the reader.

Smith forays into similar territory at times. Smith’s “Elegy” for her father Otis Douglas Smith seems to be entirely memoir of the most tender sort: “…Planted beside / me, she looked like she’d just made a check mark / on her sad to-do list: 1. Tell Patsy ’bout her daddy…” (Incendiary Art, 115). But Smith’s investigations do not stop at the borders of memory, and her love for her “bad daddy” is not the sole location of her personal truth. Incendiary Art tells a story much bigger than any one person; in fact, Smith seems insistent on widening the narrative, to include the voices of the dead, and those mourning the dead, and even alternative realities in which the dead instead get to live: ex. “Turn to page 128 if Emmett Till never set foot in the damn store” (pg 128). Smith’s sites are the history of black tragedy in America, and she resurrects all the bodies and voices: of the dead boys, (in particular) the grieving mothers, communities hushing children by showing them pictures of hate-crime victims, the two lovers “responsible” for bombing of city of Tulsa in 1921 (pg 38)–even the guns sometimes get voices. For nine pages, the only words are, “The gun said: I just had an accident” repeated over and over, stark and centered with no other words on the pages (pgs 93-110). Incendiary Art is a testament to Smith’s ability to wrestle generations worth of racial horrors into short, powerful sentences: “Jesus is no willing witness to this. The boy will be asleep” (From “How to Bust into a Black Man’s House and Take a Boy Out” pg 49). The rare and terrifying beauty of it is that it feels personal, like seeing through the eyes of a child peering at the flames of 6200 block of Osage Avenue, after the helicopter dropped the bomb in 1985. The MOVE bombing is, of course, included amongst the many topics of Smith’s explorations (pg 13), along with Rodney King, the Sandy Hook shootings, and two instances in which black fathers drowned their own daughters.

If these seem like strange events to celebrate, that is because the artistic triumph has not been properly weighed. Both Kelly and Smith revel in their craft, and as a result, the documentation of America’s terrors and the personal failures of the loved ones in the poets’ lives cannot be called angry histrionics. In fact, Smith’s very first poem in Incendiary Art expresses gratitude for the anonymity of being alive, rather than lynched and publicly upheld as a example like Emmett Till (“…But there were / no pictures of you anywhere. You sparked no moral. You were alive.” pg 6). Kelly’s volume begins with fear of love, pain from the past, and self-imposed isolation, but ends with acceptance of the future and present: “I’ve forgotten, nearly, what I’m meant / to grieve. I am lost. / Walk with me, love / that i might know what is real” (pg 62). So, these works are not negative, bitter, eviscerations of a dangerous world; they are tragic stages upon which utterly magnificent artists bare not just their souls, but their whole histories. In other words, the Tufts awards this year offer a little taste of Black Girl Magic. As Julee Wilson of the Huffington Post says, “It’s about celebrating anything we deem particularly dope, inspiring, or mind-blowing about ourselves.” And if you’re not impressed, you’re not paying attention.

—Kelly Eisenbrand

Share