The Digital Humanities and Poetry (Part II)

In my last blog post, I touched on the rising field of digital humanities and some of the basic contributions it can make to the analysis of poetry. I wrote about how digital humanities programs such as Voyant Tools can help scholars see aspects of style, grammar, and theme that may help them conceptualize a project or identify a problem within a given body of text or texts and how Scalar can contribute a multimedia edge to poems by juxtaposing their words with sound, image, and video. In this blog post, I am going to share with you how to conceptualize and begin a project that is either place-based or time-based with a digital humanities component.

When I teach my “Intro to Digital Humanities Project Ideas” class I start by categorizing projects into four main categories: place-based, time-based, text-based, and visual storytelling and presentation. These four categories put forth different sets of questions in the conceptualization phase of a project and ultimately call for a certain program or programs depending on the envisioned breadth of the final product. Determining what kind of project you have in mind is the first step towards getting your project started. So let’s start with place-based projects.

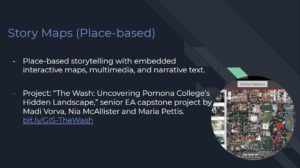

A place-based project is going to be a project that has a significant geographic component to it. For example, if you are creating a project that explores the geographic location of Kingsley & Kate Tufts Poetry Awards winners through the years, having an interactive map that can have users explore their geographic relations could enhance your position. To create a project like this you could use a product like Story Maps to plot locations, post images, and text so that your audience can experience an interactive mode of learning.

If your project is more time-based, then I highly recommend using TimelineJS. TimelineJS deploys the power of the spreadsheet and synthesizes time and media in order to produce an interactive timeline that can serve as a project in and of itself or act as a component to a larger paper or project. TimelineJS was developed at Northwestern University’s Knight Lab as a part of a larger ongoing mission to “push journalism into new spaces.” The beauty of TimelineJS is not only in its simplicity but also in its accessibility. Anyone can visit http://timeline.knightlab.com/ and follow the steps to produce a timeline of their own.

I always caution my students to consider a few things when they begin to think about if a digital humanities tool can enhance their vision. Some of the most important are:

- What is your research topic?

- What are your source materials, and how do you want them displayed?

- What do you want your final project to look like?

- How interactive do you want your project to be?

- Who is your audience?

- And, perhaps most importantly, what does the “digital” add to your story or argument?

The last question is the most salient one to my mind. It’s an important question because if all a digital humanities tool does is add “bells and whistles” to your project then it doesn’t strengthen your position. It’s perfectly okay if a digital humanities tool isn’t necessary for the work you want to do; sometimes it can be a superfluous distraction. For me, digital components typically enhance scholarship by their democratic approach to the presentation of information. By giving audiences and users a more three-dimensional way of understanding an object or space, they can get a fuller picture of the argument or story. I can tell you all I want about the geographic space of The Claremont Colleges, but why limit myself when I can also show you? You can read about all the achievements of Nelson Mandela’s life, but to put his life into a tangible piece of time you can feel the touchstones of his life and see their relation to not only time but to other events in his life. Ultimately, digital humanities methods and tools seek to address the learning and knowledge apprehension skills of everyone by providing alternative means to understanding objects, subjects, problems, and arguments. I imagine poets interested in digital humanities methods could use, say, distant-reading tools to evaluate their own work to understand it better since distant-reading programs like Voyant Tools can tell them something about their word frequency, reoccurring themes, and style. By the same token, a poetry scholar or critic could deploy Voyant Tools to understand a body of work that belongs to an individual poet or literary movement. And both creative and critical poetry connoisseur could use digital humanities programs like Scalar to make their work more widely accessible by avoiding traditional publication routes while at the same time juxtaposing their work with other forms of media.

Before you decide to begin a project you’re going to have to know how to understand your project: you’ll have to know if its a place, time, text, or visual storytelling based project. By beginning here with your conceptualization you can develop your vision into a clean and polished project that brings together traditional academic forms with cutting-edge ones. In a future blog post, I’ll discuss text-based and visual storytelling projects, how to start one, and what they can look like by sharing examples of some projects and elaborating on them.

—Jamey Keeton

____________________________________________________________________

Note: After reading Jamey’s blog, we (Emily and Genevieve) were pretty excited to try the TimelineJS tool. So, after a quick tutorial with Jamey, we created a Kingsley & Kate Tufts Poetry Awards timeline. Check it out.

____________________________________________________________________

Share