Ross Gay’s Be Holding

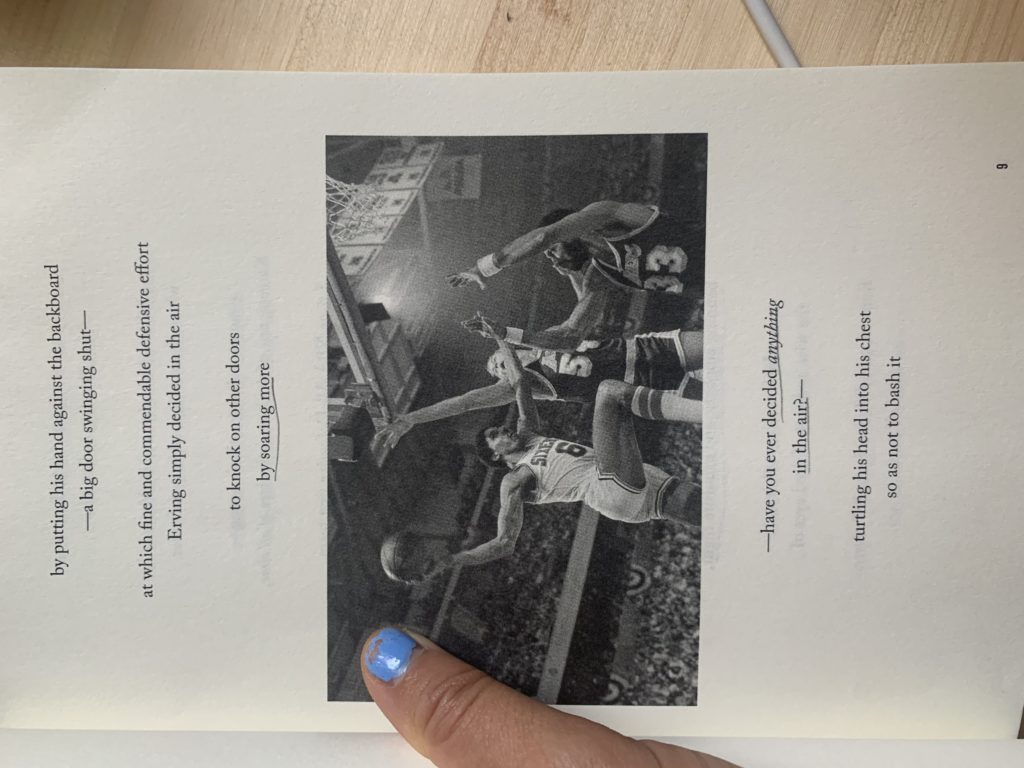

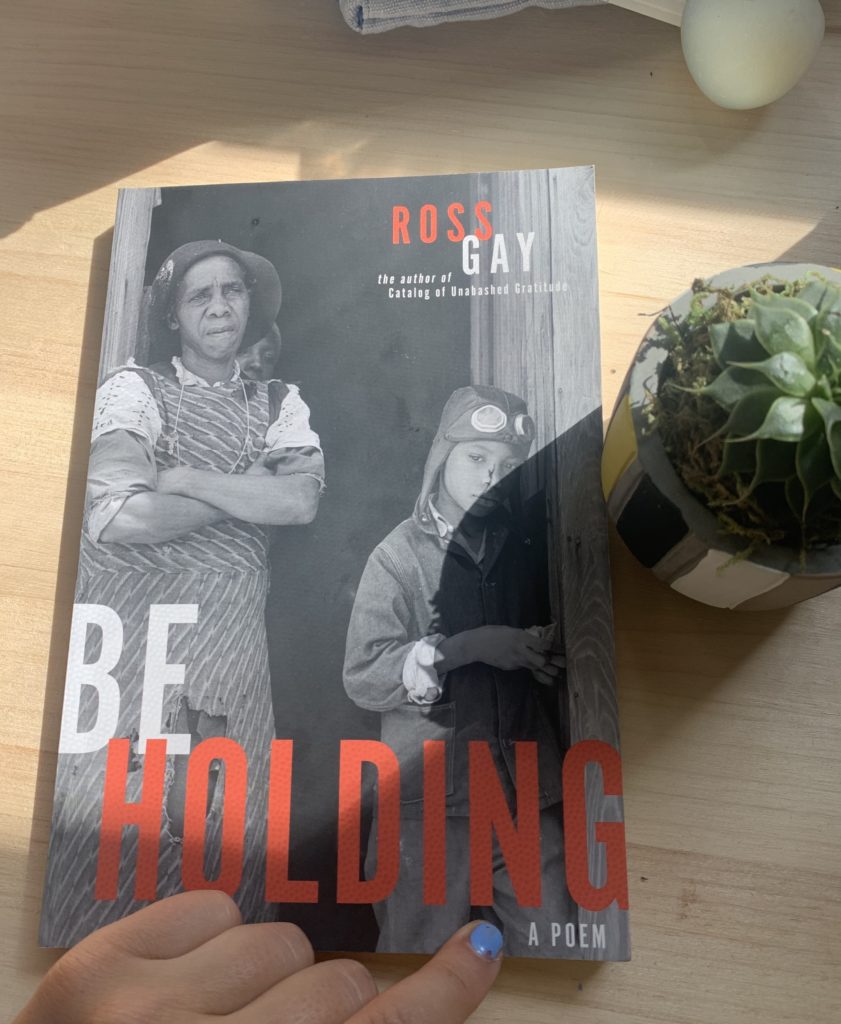

Because of Ross Gay (2016 Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award winner), I found myself somewhere I never thought I would be at 1:00 a.m.—in the annals of basketball YouTube. Ross Gay’s newest book-length poem Be Holding is prefaced by some advice: If you kids out there don’t know who Dr. J is, put the book down, do some googling and come back. Woefully uninformed about most sports history and a diligent grad student, I took to the Internet and performed my research zealously. I watched “How Good is Julius Irving Really?” (the answer is very good), and myriad highlight reels cataloguing Dr. J’s strengths as a small forward—driving, dunking, dunking over defenders’ heads, dunking from the foul line, and flying in the air for a miraculous amount of time. I watched this iconic shot, which is central to Gay’s poem, set to every song from Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah to Parliament Funkadelic’s Give Up the Funk.

I ended up here because Be Holding, like all of Gay’s work I’ve encountered, entreats the reader’s participation. Besides his formal and lyrical talents, one of the reasons I find Gay such an astonishing poet is his ability to create an awareness of an other or others. Together with Shayla Lawson, Gay co-founded The Tenderness Project, which he speaks about on his delightful interview with Krista Tippett of On Being. Gay speaks of the initiative, his investment in action with and for others, and how this is all encompassed in the word “tender.” The word tenderness implies another being that one tends to: someone who elicits an act of care. Be Holding, as the text’s epigraph from Christina Sharpe points to, similarly evokes an ongoing, loving exchange: “to be held. To behold.”

In this poem, the being held is sometimes the reader, although we are also the beholder. The speaker often addresses a you and speaks of what we are doing together, attending to the fact that another person is experiencing the poem as well. When calling attention to particularly heartbreaking realities, or lingering in a state of suspended anger, the speaker repeatedly reminds us to breathe. They lead us to places of hurt and tension, while making us aware that they know what we are feeling, that they feel it too. We see events unfold with the speaker, first watching Dr. J fly on our screens or from above, and then as the poem moves, we too are flying, falling, then flying, while being held in our flight by Gay’s deliberate and tender voice.

The reader is far from the only body being held in Be Holding. The poem and is occupied by many presences, many bodies, as well as all of those that are have touched and tend to them—the “beloving hands” that reach for and propel them into flight (72). The poem searches for and creates moments of connection as it swoops across time and space and floats midair, protracting moments of reaching and holding; of loving and lifting; between grandmother and child; between schoolyard friends; between light and shadows.

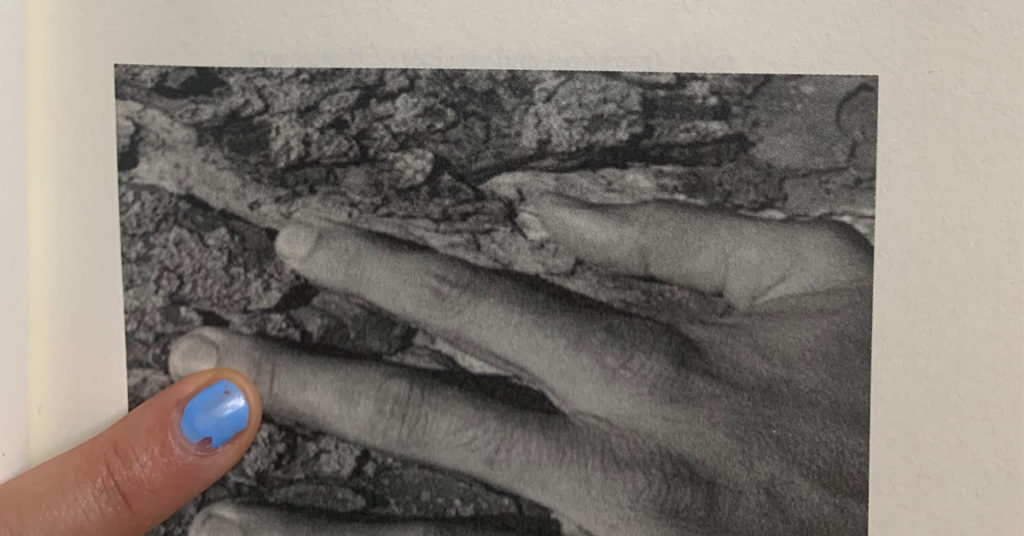

The poem explores the hairline distinction between falling and flying, and especially how Black people hold one another in flight, even within conditions of cruelty and constriction. Full of attention to photographs, the poem reaches for particular Black bodies that have been captured on film—shot by cameras—and is acutely attuned to the violence by affixing a body through representation and in gazing at and commodifying Black suffering:

I wonder if, no,

I wonder, how,

I too am a docent

in the museum of black pain (41)

Whereas the poem doesn’t resolve this worry, it does show how the loving attention of the speaker bestows on these images and changes what the gaze does to the bodies, making the difference between beholding someone and holding them down:

it does not capture or shoot anyone

does not fix anyone

does not catalog or corral

or specimen or coerce

but holds them both

in their flight (96)

Gay’s poem, in many ways, is taking these still images, these captured bodies, and reanimating them. The dynamic gaze and careful imagination of the speaker puts these bodies back in motion, and then stands back and marvels at their flight.

Told in a series of couplets, Be Holding is a process of floating—flying and falling interchangeably—and trying to reach for something, someone, to hold onto in the air. In this poem, as in Julius Erving’s extraordinary flight to the basket, the reaching for and holding one another does not stop us from falling, but instead, actually may make us fly, who knows for how long:

we in here talking

about the reaching

that makes of falling flight,

do you see

what I’m saying,

we’re in here talking

about holding each other

which is a practice, we

talking about holding

our breath,

how long have we been,

and how can I be

holding yours

and you

be holding mine,

this is my question (90)

To me, Ross Gay’s ability to find, create, and make tangible, the connections between people is all the more miraculous—or rather “amazing but not miraculous”—during these months of isolation (5). In 2020, I can no longer take for granted that I can be near and hold my loved ones, and the tender touch Gay endows on the subjects and objects of his attention, including the reader, feels all the more precious. He insists we ask, even in these moments of free fall: What would change if we were to practice reaching for, and holding, one another?

—Lilly Fisher

Share