Reading Diana Khoi Nguyen’s Poem – I Keep Getting Things Wrong

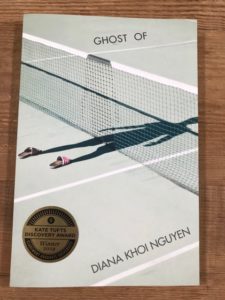

I am here! School is back in session, spooky season is just around the corner, and I have returned as one of two(!) bloggers this fall semester. I wanted to start out talking about a subject I didn’t get to over the summer: the Kate Tufts Discovery Award winner, Diana Khoi Nguyen. I had the pleasure of attending a dinner at CGU President Len Jessup’s house last semester and listening to her discuss her poetry there. Ghost Of is a fantastic collection and it feels like every line is seeping with meaning. It is haunting.

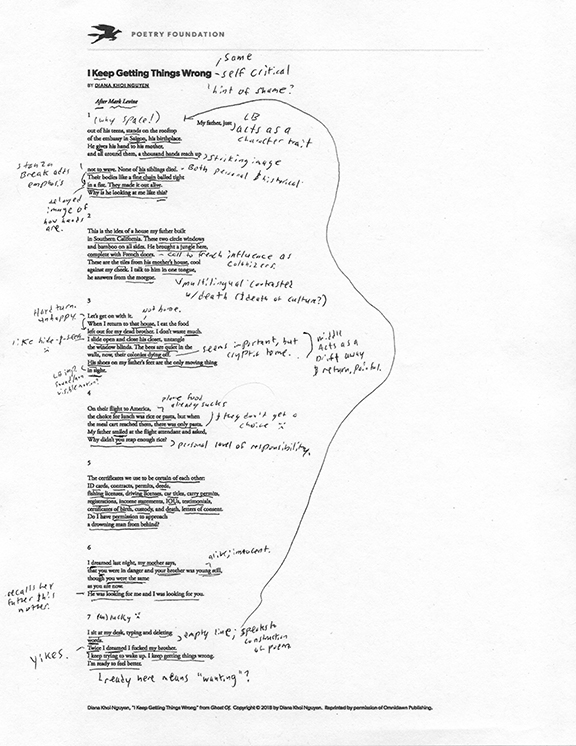

I wanted to give a poem of Diana’s the same treatment I gave Dawn Lundy Martin’s. So I popped onto Poetry Foundation and perused the poems from Ghost Of that were there. I landed on “I Keep Getting Things Wrong” because it has aspects that every person can understand, while also digging into the personal, internal space that nobody can really understand (and, partially, because the title is a big mood). Here are my notes:

Whoa. Ok. So there’s a lot to this poem. To start us off: I looked up Mark Levine’s role in Diana’s work, and came across this cool article she wrote on Body about Levine in 2014. It’s personal, and I feel like it scratches the surface of what that “After Mark Levine” might have meant. Thank you, Internet.

I have decided to focus on section 3 of this poem, because it marks the hardest turn in the poem to me. Let’s get on with it is, perhaps, the key line. It comes off a heavy closing line from 2, about the narrator’s father’s death (or perhaps, him at the morgue, viewing the narrator’s brother?). The line itself acts as a change-of-pace that hits the ground running—whereas section 2 is a slow flowing stanza of deliberate imagery, this line is a sharp, 5-syllable sentence. The following several lines use the reader’s natural emphasis (or at least, my natural emphasis) to heighten the narrator’s disdain for the situation. The house becomes that house. The food is left out for her dead brother. She doesn’t waste much. Three big ideas get crammed into two short lines, where the reader can feel her vehemence for having to recall the moment to another person, as though each person reading this poem was pushing the knife a little bit deeper in her chest.

And then she shifts to this innocuous, mundane image: “I slide open and close his closet door.” It is almost robotic, as though it has been done a thousand times. As a sibling, especially an older sibling, I read this like a game of hide-and-seek. My brothers used to hide in two-three places of the house regularly, and at the start of the game I would quickly check each. It would only take a moment or so to swing the door back, glance around, and then snap it shut again. Here, her body moves mechanically, as though she didn’t even realize why she was opening the door.

Just like that, I got to realize part of what makes this death so hard for the speaker. It isn’t just a thousand disembodied hands reaching out for help, but her brother: a brother whose memory is so fresh in her mind that her body can’t process that his disappearance isn’t a game.

Anyway. That’s it for today. Keep an eye out next week for my blogger-in-crime (partner-in-poetics?)’s first post. Oh, and be sure to pick up a copy of Ghost Of. Do it. Click the link. You’ll thank me later.

–Cassady O’Reilly-Hahn

A Moment of Zen:

Cat Under a Chair

While you lick your lips

and paw at the wooden legs,

I’ll sit and pay bills.

Share