Read This! “Don’t Call Us Dead” by Danez Smith

Who am I to write a review?

No, really. I am not a prophet; I can’t say with any certainty (beyond posturing) what anyone ought to be reading. Of course, it’s a cop out to say that “it’s only my opinion.” If that were true, why turn it into text? Why pass it around? The reason I ask is because occasionally, I stumble upon a book that I think everyone should read. But I don’t want to make subjective claims. I want to say something more generalized, because the universal is the persuasive, right?

But when I stumble on a book I think everyone should read, my reasons for wanting others to read it are subjective, no matter how I organize my arguments, no matter what sources I reference, or what discourse I invite. People will read what they want to read, or they will take my word for it: no more, and no less. But the question of subjectivity matters because I have a feeling I am not the right person to tell people to read this book.

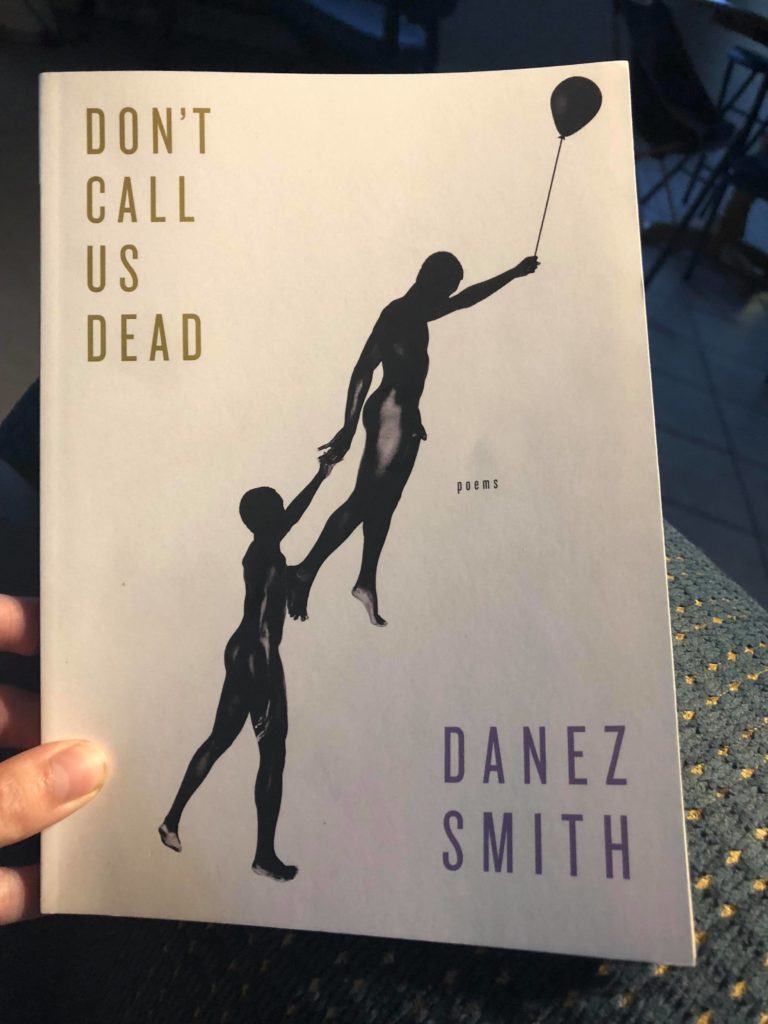

Don’t get me wrong, I am still going to tell everyone to read it. Don’t Call Us Dead by 2016 Kate Tufts Discovery Award winner Danez Smith is plaintive, fierce, lonely and so beautiful I swear it could hammer compassion back into a heart. If there were ever so vulnerable and bittersweet and indictment of white civil society, I couldn’t point to it. I know we read to confirm our biases, but if Smith’s poetry can’t melt stone into water, no force in the universe can.

I can’t help but to feel like a voyeur when I claim this, however. Smith’s confessional text lends itself to that feeling (ex. “a. the sound i made when he was most inside me” from “O nigga O”). From their discussion of HIV, to their musings about the many uses for Vaseline (hint: not just for chapped lips), to their re-imagining of a private heaven for murdered black boys, Smith is relentlessly vulnerable. However, my quandary is not only because Smith has granted their readers access to such a private realm. I also fear that it is arrogant and intrusive for me to point the spotlight.

Of course, we can assume Smith wants all of us to marvel and be consumed by their poetic acumen and celebration of a heritage of traditions. They references a diverse and celebrated cadre of artistic fore-bearers: Erykah Badu, Lucille Clifton, Richard Siken, Beyoncé, Drake, Chinaka Hodge, and others. But my place in this celebration may be on the sidelines. If Smith offers their tragedies—societal and personal—for our consumption, ought I take the gift and be grateful? Ought I say “thank you” and nothing more? Ought I let a black person speak for themself, rather than assume they need to borrow my voice?

And what if I alter what I find? Don’t Call Us Dead is full of imagery of rivers (“my veins—rivers of my drowned children/ my blood thick with blue daughters” from “elegy with pixels and cum”), as well as imagery of oceans, tears, and rain. However, it is also full of imagery of sex, violence and death (“they want us to fuck more than they want us to exist, kid” also from “elegy with pixels and cum”). If I write a review that softens the impact by picking and choosing what parts I thought were most palatable and leave out what I thought was challenging, I have undone Smith’s central project. Even if I mean to be honest, I may reproduce the very system that inspired Smith’s wrath, and their grief. I was born into it. I can’t escape anymore than they can.

Still, ultimately, I want everyone to read this book. My favorite poem in the collection, “dinosaurs in the hood” is a riotously rich and compelling piece: equal parts hopeless rage and burning hope. The best description of the poem is a line from it: “children of slaves & immigrants & addicts & exile—saving their town/ from real ass dinosaurs…” This poem is a perfect example of Smith’s imaginary play with raised stakes. In a microcosm, Smith creates the thing they demand. They describe a movie about dinosaurs, and about black people saving their own neighborhoods from a Jurassic Park–style invasion. But they carefully qualify the wish: “…But this can’t be/ a black movie. this can’t be a black movie. this movie can’t be dismissed”. Seemingly paradoxically, this wish represents the hope for stories about black people to not be stories about black people. But the paradox dissolves with a single consideration. Smith is just asking for their family, friends and neighbors to be seen as heroes—human heroes—not separate, categorized, “other” heroes. The wish is plaintive, because the “possible, pulsing, right there” hope is for blackness to be seen and celebrated, rather than mourned or ignored.

This, ultimately, is the success of Don’t Call Us Dead. Danez Smith’s unflinching humanity and glorious, lyrical poetry (and poetic prose) spin dreams into something that can be held in hand. For though I did cry while I read it (in a McDonald’s no less, with a judgmental woman staring at me and possibly taking pictures with her phone), I also made the connection.

Every mention of “whistling” recalls Emmett Till: a 14-year-old black boy who was lynched in 1955 in Mississippi for allegedly whistling at a white woman. Every mention of “breathing” recalls Eric Garner: a-43-year-old man who was strangled by a cop who put him in a chokehold in 2014 in New York for allegedly selling single cigarettes from packs without tax stamps. Smith discusses HIV; they even give the statistics (from “1 in 2”: an estimate of 1 in every 2 black men who has sex with men is diagnosed in his lifetime). It is impossible not to know what Smith means when they say they are “thinking about blood” after that.

But Smith does not bury these many dead and deferred. Instead, they imagine a heaven where “the forest is a flock of boys/ who never got to grow up// blooming into forever/ with afros like maple crowns”. These boys “say our own names when we pray”. Neither Smith nor their subjects ask for our condolences nor certainly our pity–only that we take the time to revel in the beauty…which is why, I beg you, my dear reader, to pick up this book.

—Kelly Eisenbrand

Share