Pearls, Diamonds and Dogs, Poetry and Love

The summer before I turned sixteen years old, I was enlisted by my aforementioned Poet-Aunt Charlotte to dog and house sit for her fellow prose companions, Pam and Bill. I remembered them vaguely from times when I was little, growing up in the Art House surrounded by Tucson artists and authors, the smell of oil paint and chlorine in my hair from the pool I learned to swim in.

Pam, willowy and doe eyed, absolute drapes of blonde hair past her shoulders, and Bill, unbelievably tall to me as a child and still impressively so as an adult, scruffy with the kindest smile, and their beautiful dogs. Zazu, Sonoran brown with a lot to say, and Happy, a white wolf with a crooked grin and a head that would lay in your lap. I house sat for days, spending a week or so alone in their Tucson home, made of hewn wood and desert brick with open windows to the wildlife and more artwork and books than my eyes could take in. Bill gifted me, before they left, with a typewriter I have to this day. I woke up early each morning to watch the sunrise over the baking hills in their backyard and type out the poems I would later get into undergraduate school with.

This past summer, before my move to California for graduate school, I dog sat for them again. Happy had since passed to hike through mountains and chase birds elsewhere, and I was greeted by Zazu again, and Mojo, the absolute largest wolf I have ever met, jet black with almond eyes that are far too human, a love for running in circles with his mouth wide open and sleeping on my feet for protection.

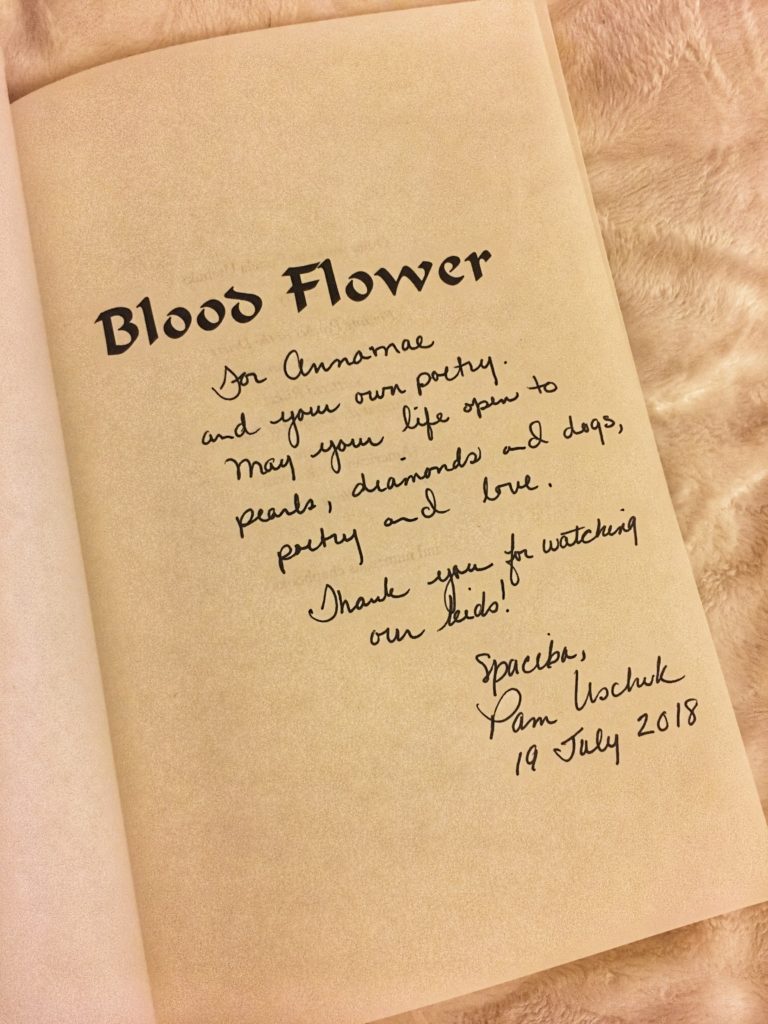

Pam and Bill have been constant figures of inspiration in my life, supporting me through school and travel, encouraging me on my path of poetry and publishing, watching me grow and helping me along the way. When I left their house this past summer, and subsequently left Arizona altogether, they both gifted me their books of poetry, inscribed with hopes for my journey. I want to share their pieces here, starting with Pam, and then later Bill.

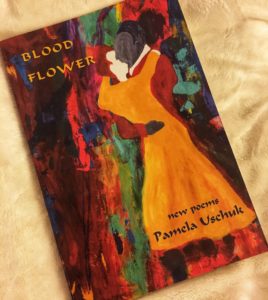

Pam published Blood Flower in 2015, the front over splashed with red like pomegranate juice and streaks of turquoise, a mustard yellow and navy blue couple embracing, dancing with their arms wrapped around each other, beautifully faceless, art made by Pam’s sister Judi Uschuk-Stahl. It’s vibrantly fitting for a book of poems on Pam’s family, a family of immigrants, and a family of people she loves fiercely and those she has lost. Pam, as she has often spoken of, knows the pain of losing a sibling, a limb taken off, and her presence on this path of mourning has been a comfort for me on mine.

In the third section, “Talk About Your Bad Girls,” there is a poem titled, “The Dead Unburied By Spring” where she describes a mare they found, golden under a tree, a tree under which the horse would later die and dissolve. Pam writes,

The mare died alone under distant stars

the way my father and brother died alone, far

from those who raised them, who kissed their skin

alive, after sending us away whose love

would have moored them to earth longer than

their hearts could bear.

Collapsed beneath this tree, star bound and in solitude, this mare left, the same gust of wind, the same nighttime sky taking her as these two distant men were taken, one by one and all at once. Those that are left behind hurt, more than they can bear, but not nearly as bad as it would have hurt to force those already leaving to stay.

In this poem, Pam asks what I ask myself every day,

Why do I imagine her death was born

at night? My only brother and father

left near midnight, decades and a continent

apart. How can I ever shake

the wet ash of their leaving from

grief’s ulcerated cramping?

I’ve come to believe that all death is born at night, even if it must hold off those desert sunrises I love to watch so it may take and leave. There are years between Pam’s father and brother, and miles of land and sea, that death does not mind birthing across to gather his pearls.

Pam’s poetry is full of history, more than any family tree weighed down with too-ripe apples could hold, loss that can only be understood in the spring bleached bones of a horse you loved far too much. This book is ripe and bleeding, an Arizona cactus in the moonlight drawing in as much monsoon rain as it can before the sun comes up. This is the poetry of a woman I care about dearly, whose summer house and smirking wolves I’ve grown up loving. Pam understands, above of, how quickly grief can swing from heavy like a brewing rainstorm to chalky like a handful of Tucson dirt. It seems, no matter how hard I shake or how many oceans I bathe my hands in, there is no losing the wet ash of brothers.

—Annamae Sax

Share