On Lineage, Loving Who Came Before

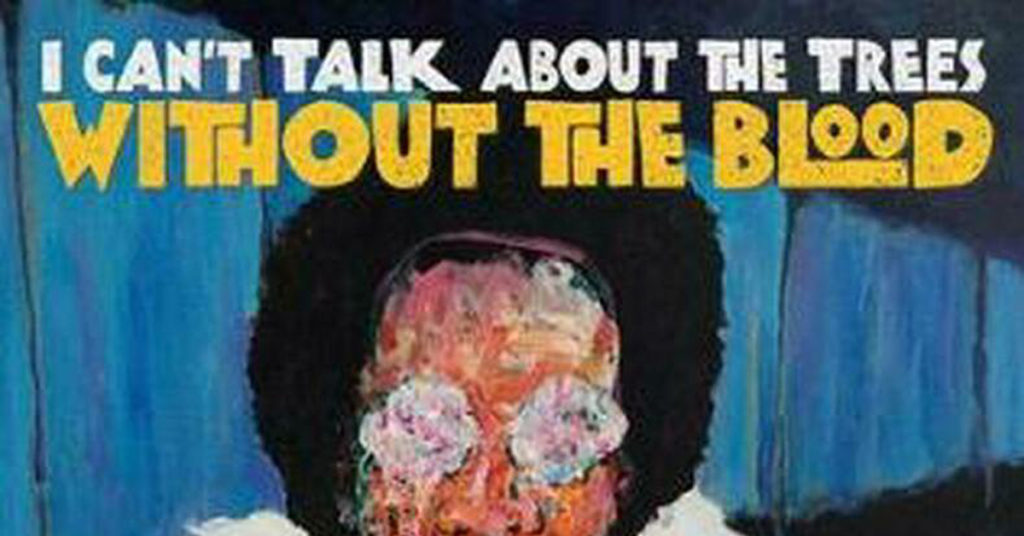

Recently, I reread 2020 Kate Tufts Discovery Award winner Tiana Clark’s I Can’t Talk About The Trees Without The Blood, and the poems titled “Conversations with Phyllis Wheatley . . .” prompted me to think about what it means to know your lineage as a poet.

In the feature series “In Their Own Words,” for Poetry Society of America, Clark writes about how she was asked to trace her “literary ancestry” while in grad school. Clark says about Wheatley, “She was the first Black female poet, and the firstness mattered to me.” Clark interrogates how communicating with Wheatley essentially helped her “grasp at something fresh . . . [at a] revelation about [her] own life, something [Clark] couldn’t say or pinpoint without [Wheatley’s] presence percolating the watery heat inside a specific poem.”

I’m enamored by this idea that communing with a literary forebearer can help crack open one’s own subconscious—access those epiphanies that are hidden away. It’s like having a mini-therapy session with a ghost. This cathartic exercise also reflects how significantly the past and one’s history, or the idea of history itself, figures into the life of a poet.

Other than the few poets who think that the world does revolve around them, most poets understand that their poems’ speaker does not exist solipsistically, and that self-knowledge in a poem only actualizes in relationship to other people, ideologies, etc. So using the framework of a conversation—a series of poems that assumes a perpetual back and forth between Clark and Wheatley—showcases the speaker’s remarkable insights in light of a poetic inheritance. The speaker does not arrive at realizations and musings alone; she is guided, taught, and raised.

Invoking one’s lineage is more than just paying homage and respect—the poet understands how their work exists within a tradition that precedes and will continue after the poet is gone. Robert Pinsky writes about “how the medium of poetry is the human body,” and, though he is referencing the vocality and bodily qualities of poetry, this understanding that poetry is a human endeavor applies to how we might think about a poetic lineage.

No poet exists without the poet who came before, and the one who will come after—poetry that is written in community with others, in recognition of how the past and present are kindred, will be poetry that exists as a part of a greater body, stronger for existing as a collective. A poet is always better for understanding and connecting with those who came before because their work will reflect more than themselves.

—Stacey Park

Share