On Impossibility, Wandering, & Emptiness: A Conversation with E. J. Koh

SP: What is your most optimal way to write a poem? What is your process like?

E.J.: A hybridization of kishōtenketsu (起承転結), or in the Korean, giseungjeongyeol (기승전결), has been hovering over my newer work. It appears to be the root of a feeling I’ve been looking for since I was a child. My mother would put on tapes of Korean fairytales and nursery songs. I would try to re-tell them, and nobody could make sense of them but responded with intense feeling. In kishōtenketsu, there seems to be no direct conflict, turn, or resolution. The narrative or poetry structure exists to be lived in, like the way we enjoy music, and we don’t need to arrive anywhere. The beginning and end can be polarities of awareness, or there can be no changes at all. The end is only the invitation for the reader to imagine the connection between the events. My process has been thinking about a sense of magic, of impossibility. When I sit down at the moment to write, I want to feel that what’s coming is unreasonable, uncontainable.

Do you find that you are most comfortable in a particular mode of writing or is it different with each poem? I ask this because I think you are a master of the short-form, lyric poem. I think I am an overwriter/oversayer, so when I try to improve that in myself I look to you and other writers who can say a thing so economically, clearly, and evocatively. The first poem of yours I read was “Confession” from Verse Daily and it continually floors me and teaches me.

Thank you for asking, and I don’t know if I have an answer. In the poem you mention, “Confession,” I’m unconsciously wandering around temporal and linguistic modalities. What we know about the Korean word for trauma, han, are its temporal and linguistic elements. Temporal—as in the accumulation of historically specific violence. Linguistic—as the naming of the word han for which there is no English equivalent. But I believe han is universal and can be felt by anyone. Han is described as a deep sorrow, at times, bringing on physical symptoms of heart palpitations and fainting. I would add that han is the gap between what can and cannot be resolved. We talk about han when we talk about colonial violence, about the comfort women, about the Zainichi, about the Jeju Massacre, about absent reparations. What makes han culturally specific is that the Korean has a word for it. “Confession” starts in New York City where, as an adult, tired after work, I would drink the water from the showerhead to feel full before going to bed. The next couplet, my footsteps as an adult are treaded by the footsteps that belonged to my younger self. We cross into the Korean and their translations into the English—the complicated relationship between the two countries also emerges from the act of translation. The language shifts into “bad English,” which Cathy Park Hong calls her heritage as an Asian American, and I connected to that deeply. The last few couplets, I’m in my childhood bedroom, eating the stucco dropped from the ceiling to my face—a mirroring of the adult drinking the water rushing out the showerhead. We have here a mode of han and hanfulness through time, repetition, a gap, and instead of an ending, the turn is a separate and simultaneous event, an awareness about writing, a relationship: “I started to tell stories because/ my parents lived so far away.”

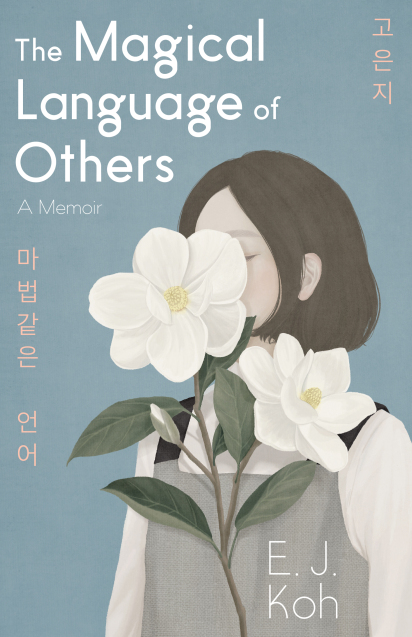

How was the experience of writing your latest memoir, The Magical Language of Others?

When I was in the last stages of the memoir after seven years of translation and writing, I was also in the second year of my PhD, and at the same time, in a writers room for a television show, working bicoastally from Seattle and New York City. If anyone saw me, they might have worried, but I’d never felt more at ease. I was meditating an hour every morning and evening. In between, I was researching Korean history and trauma as I was writing scripts and pitching for the screen. With these things combined, I learned and wrote in quiet symbiosis. Working on one task, I was working on all tasks, and that relationality was clear to me. It was the best time for me to complete the memoir. The memoir naturally inherited elements of history, translation, poetry, screenwriting, and dance. There was a roundness to my work that came with new meaning, and my job was to be grateful. Looking back, I almost can’t believe how supported I was during that time.

How do you approach writing about yourself through poetry?

Hayao Miyazaki talks about ma in his films. It means “emptiness.” He describes it by clapping his hands, and saying, “the time in-between my clapping is ma.” It creates breathing space without moving the story forward. It’s a pause for the sake of pausing. Ma helps me notice the interstices between moments. When I’m writing a poem, I’m wondering about ma and silence. I’m spending time alone. It just occurs to me now that maybe, my mind is always full, and poetry helps me reach ma, emptiness. If everything in the world was perfect, if my mind and conscience were empty and clear, would I write poetry? I don’t know—every poem feels like the last one I’ll ever write.

—Stacey Park

E. J. Koh is the author of the poetry collection, A Lesser Love, winner of the Pleiades Press Editors Prize for Poetry, and the memoir, The Magical Language of Others. Her poems, translations, and stories have appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Slate, World Literature Today, and elsewhere. Recipient of Prairie Schooner’s Virginia Faulkner Award for Excellence in Writing, Koh has accepted fellowships from the American Literary Translators Association, Kundiman, the MacDowell Colony, and others. She earned her MFA at Columbia University in New York for Creative Writing and Literary Translation. Koh is completing her PhD in English Language and Literature at the University of Washington in Seattle. She tweets @thisisejkoh.

Visit her website to read about her work.

Share