On Cutting Photographs and Missing Brothers

This past spring break, I boarded the late night train to Tucson again, carrying a shopping bag of cacti and clutching a poetry book in my hand. I was heading home for my late brother’s thirty-first birthday, and I brought with me to read Diana Khoi Nguyen’s Ghost Of. I ate this book alive, more than once, but it has taken me awhile to write about. Maybe I was digesting; maybe I was trying to let the text fade from my mouth a little bit before I tried to sound it out; maybe it just hurt too damn bad.

Diana Nguyen’s Ghost Of is our 2019 Kate Tufts Discovery Award winner here at Claremont Graduate University, and her book is so much more than poetry, so much more than just visuals. Her book is a tombstone, hand carved, and it feels just as heavy as the one I carry around.

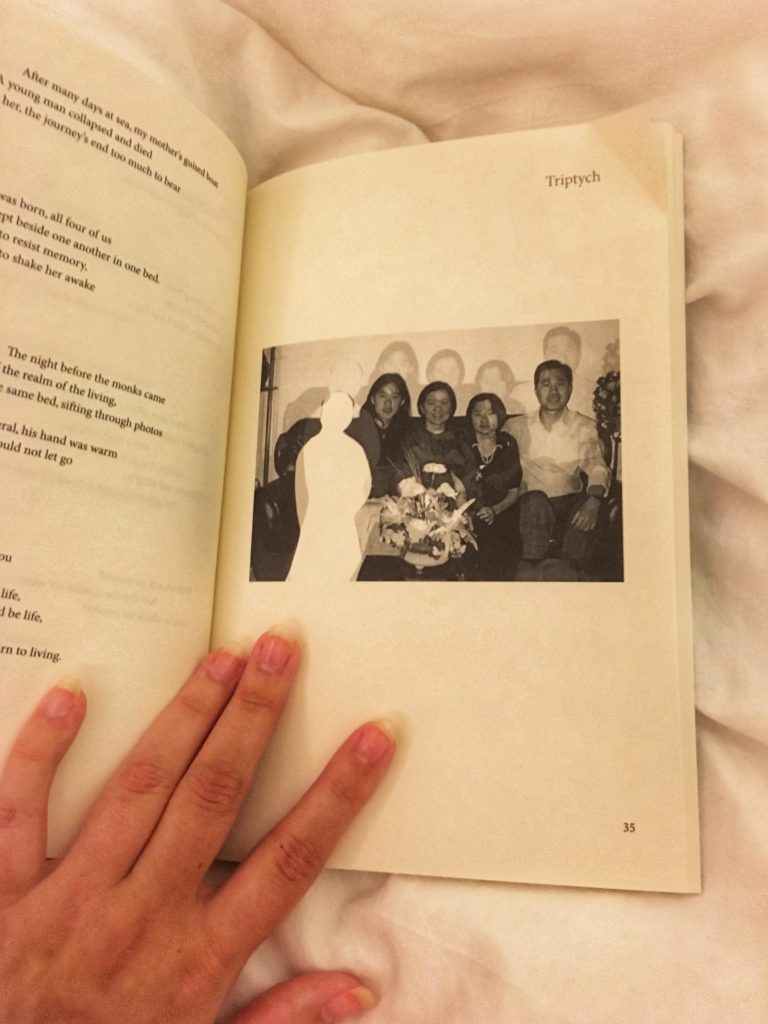

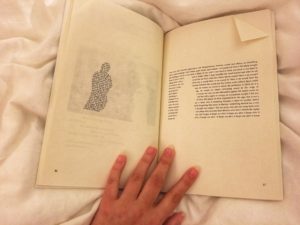

You see, Ghost Of is about Nguyen’s brother, Oliver, who took his own life. I know a little too much about dead brothers, a little too bleeding, a little too burnt, a little too late. Over the span of various pages, in “Triptych,” we see pictures of Nguyen with her siblings, childhood photos, in which Oliver is cut out. The space he leaves behind is gaping, and sharp, and draws your eye like a train wreck. This plays out again and again throughout the book, the cutting out of, the making of space you do not want. Some of the poems echo this, with whole chunks sliced out and placed on the next page, poems with holes that ache and weep, like what you see on page thirty-six and thirty-seven: Oliver, cut out of the poem, words in the shape of his body, misplaced.

In the title poem “Ghost Of,” Nguyen writes, “Is belonging and fulfillment possible without family? No. Is it possible with family? No. / You cannot connect if you keep answering no. / You cannot keep your brother alive if you keep your mouth shut. / You cannot keep your brother alive.” In the aftermath of this cutting out, of this removal of Oliver, of a brother, Nguyen’s poetry grapples with the concept of connection, of what is left, of what can be had with a sliced up family. Can you ever truly belong with your siblings, your parents? Can you ever do it without them, or will you always be finding cut apart photographs? If you always answer no, will you ever get a different answer? Most cuttingly of all, where there is no question: you cannot keep your brother alive. That will never happen, and that is pain in its purest form.

In “Exodus,” Nguyen writes, “The night before the monks came / to usher my brother out of the realm of the living, / we gathered on the same bed, sifting through photos/ and stories of him. / At the funeral, his hand was warm / where my mother would not let go.” I read this poem, over and over, digging my nails into the pages, sitting on my old bed in my old room, the bed I sat on the night I found out my brother had died, and sorted through our photo albums to find the best childhood pictures for his funeral. When a brother is cut out, cut clean, photos and stories are the only hands you have left to hold.

Diana Nguyen mourns in Ghost Of, she reaches to a brother she can no longer touch, past cut out photos and time and a different realm, a reach to love and understand and say goodbye. This kind of reach is exhausting, to the core, and is one a sister can never finish, but merely maintain, and try to find the poetry in the missing pieces, assemble something of a funeral dirge, but lighter, stronger, more like a sibling.

Back in Tucson, I listened to my brother’s last voicemail on repeat, a new cut every time, and tattooed his final words to his siblings on my ribs, wanting it to hurt, wanting it to stay. Alright, love you. Bye. When brothers leave, the poems we write about them are all we have.

—Annamae Sax

Share