“A Mouth that Knows Itself”: Beyond the Antipastoral in Vievee Francis’s Forest Primeval

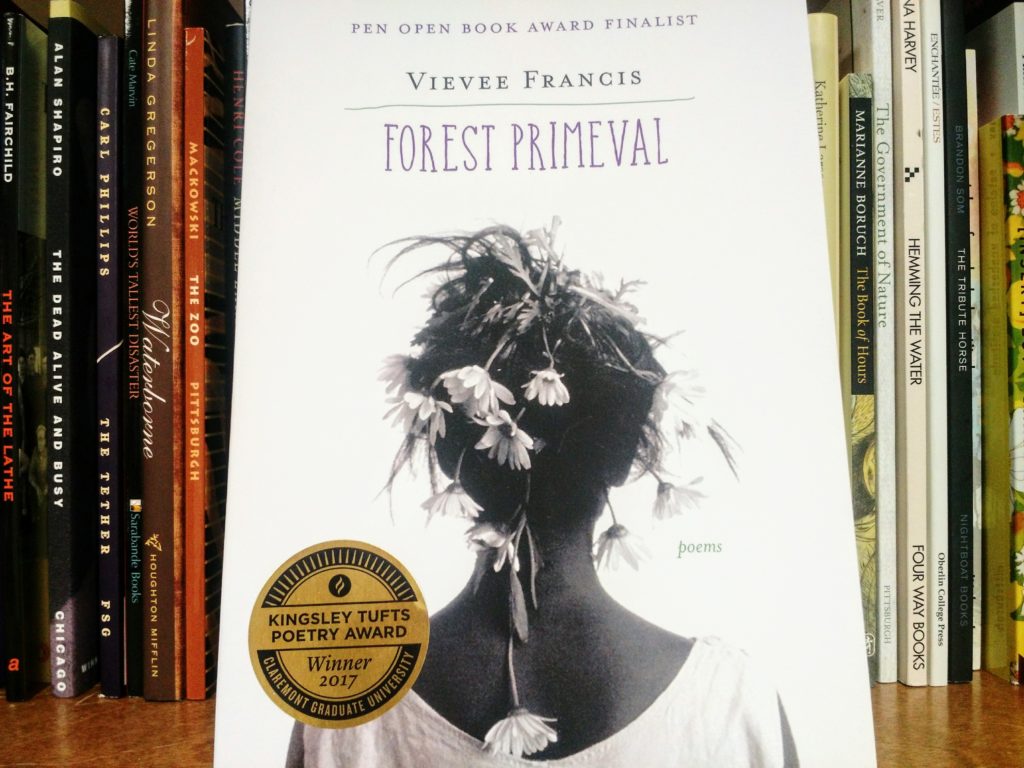

Reflecting on her move from Detroit to western North Carolina, Vievee Francis has talked about the harshness of her new environment as a sort of inspiration for her recent book of poems: “Everything was terrifying; absolutely nothing was pastoral. Nothing was romantic for me. Everything bit, or could bite.” Confronting this new “pasture” is where Forest Primeval begins, but the poetry goes much further. In January of this year, Forest Primeval won the 2017 Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, making Vievee Francis the 25th recipient of this prestigious prize. This award, along with the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award for Poetry that she won last year, speaks to the artistic significance of what Don Share has called Francis’s process of “reclaiming modernist and feminist legacies of poetry.”

Many of the reviews of Forest Primeval have focused on the antipastoral aspect of the work—a theme which is initiated by the first poem of the collection “Another Antipastoral” (3) and continues throughout the various forests and natural landscapes of the book. But in my reading, I found that the antipastoral-ness of the poems functions mostly as a starting ground from which Francis explores many profound themes and motifs of human life. It is beyond the antipastoral where I encountered what interested me most about the collection: the many mouths of Forest Primeval.

While the first line of poetry in the book (“I want to put down what the mountain has awakened”) draws the reader’s attention to the mountain, there is in the shadow directly under this line a speaker with a “mouthful of grass.” The speaker’s sense of what the mouth wants but cannot say is felt as a “bleat in [the] throat” and in the “fantasies” not yet articulated but aspiring “to cud and up from this belly’s wet straw-strewn field” to land upon the page.

This first mouth precedes the many mouths throughout the book that are yet unfulfilled in their desires. There is the “heart-shaped mouth” that becomes “swollen […] shut” in “Taking It” (14-15); the “hungry […], empty […], insistent mouth” of “Epicurean” (30) that longs to “surrender”; and the “mouth of webs” in “Her Mouth” (78) that remains unkissed, but “still so prettily shaped / for the taking.” Mouths fill the pages of this book, but not just any mouths. The poetry in Forest Primeval focuses on the mouths that would ordinarily not call our attention: mouths that cannot speak, eat, or kiss.

Upon first glance the word mouth appears secondary to the sweeping landscapes of the antipastoral, but Francis’s interest in the mouths of her speakers and subjects becomes less subtle as the poetry moves forward. Near the end of the book, the poems “Her Mouth” (78) followed immediately by “Consider the Prince as He Considered Her Mouth” (79) remove any nuance. The poet forces the reader to confront the significance of the mouth (or mouths) by placing the word in the title of her poems.

Beyond the word itself, mouths appear not just where they are directly named but also in the collection’s preoccupation with swallowing, eating, and licking, as well as in the constant mention of hunger. The last lines of the last poem confirm the significance of these mouthy actions when the speaker says:

And though a mother may destroy,

She too sees fit to create beauty

That would eventually grow into forms

I would swallow if I gave in

To my hungers. Nothing will come

Of this womb. But, up from my wounds—

From this goat’s body—

Up from my wood-smoke lungs, from

The milk of me, comes a song, a melody

To open yours, then lick them clean (“Chimera” 92).

In these lines the mother (creator) fears what the satiation of her hunger would do to her creation, and yet, she knows that from her wounds she will use her mouth to heal the wounds of others. The mouth, though left unfulfilled in some regards, ultimately becomes a healing power.

Recalling what Francis herself said about her move to North Carolina, I remember that she has always placed an emphasis on the mouth: “Everything bit, or could bite,” she said (presumably talking about the bugs and insects of North Carolina). Mouths full of fears and desires—in nature, in love, in a poem—is at the core of what Francis’s collection has to say, though many of her speakers and subjects cannot yet articulate any of it for themselves. Francis’s readers are fortunate she’s acquired “a mouth that knows itself” to be able to say it all.

—Ashley Call

Share