Layli Long Soldier: Respecting the Sentence

Layli Long Soldier is an Indigenous poet, writer, feminist, artist, and activist, and a member of the Oglala Lakota tribe. She earned her Bachelor’s in Fine Arts from the Institute of American Indian Arts and her Master’s at Bard College. She mostly grew up in the Four Corners Region of Arizona, where she now teaches English at Diné College of the Navajo people, the first tribally-controlled college in the United States.

Long Soldier’s indigeneity is central to her activism, her work, and her poetry. Oglala Lakota means “to scatter one’s own” in the Lakota language. Her poetry has deep roots within her Native identity, her own poetry scattered beautifully with the Lakota language and her perspective on her culture. She ties in Native lore seamlessly, and advocates against the continued, systematic oppression of indigenous populations.

I first came across Layli’s work my senior year at the University of Arizona in my class on Indigenous Women and their literature. I had found her poem “38” when looking for poetry in another class, and then dove into her work for a presentation in my Indigenous Women class. “38” is about the 38 Dakota men who were hanged under order of President Abraham Lincoln, the largest mass execution in our country, though rarely recognized. Long Soldier makes sure to note that this took place the day after Christmas, the same day President Lincoln signed into effect the Emancipation Proclamation, and how only one of these actions of his made it into the movie of his presidency. These men were hanged due to the Sioux Uprising, which occured in response to being forcibly removed from their land and starved, with no support offered and traders refusing to trade food with the Natives.

There is a quiet sarcasm, a patience and self awareness to Long Soldier’s poetry, one that echoes with the oral tradition of indigenous communities and the exhaustion of a people who have survived genocide only to have it wiped from history books. Long Soldier’s poetry is resigned to teaching people, and it wants to do more than educate. It wants to change. “38” reads:

One trader named Andrew Myrick is famous for his refusal to provide credit to Dakotas by saying, “If they are hungry, let them eat grass.”

There are variations of Myrick’s words, but they are all something to that effect.

When settlers and traders were killed during the Sioux Uprising, one of the first to be executed by the Dakota was Andrew Myrick.

When Myrick’s body was found,

his mouth was stuffed with grass.

I am inclined to call this act by the Dakota warriors a poem.

There’s irony in their poem.

There was no text.

“Real” poems do not “really” require words.

Long Soldier fluidly reevaluates what exactly it takes to make a poem, looking at the grass stuffed inside the trader’s mouth and seeing the poetry in that justice. It doesn’t take words to write a poem, it doesn’t take text: it takes having something to say.

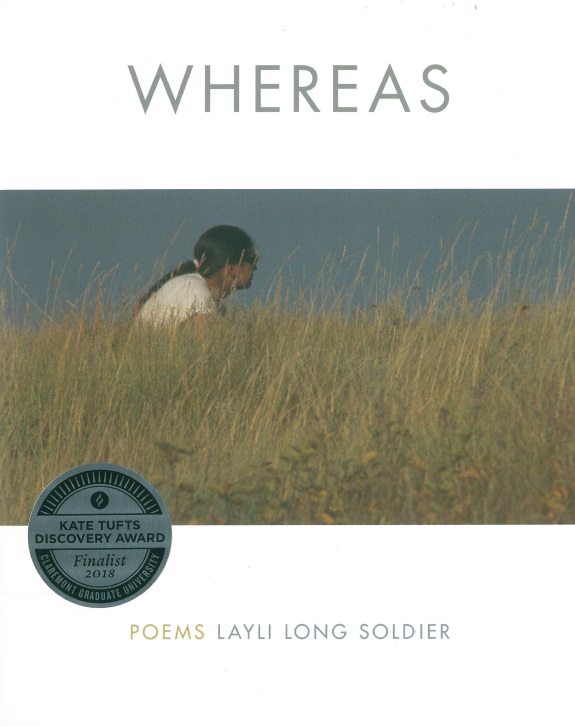

“38” features in her book of poetry, WHEREAS. The book, a finalist for the 2018 Kate Tufts Discovery Award, is in two parts: “These Being the Concerns,” and “Whereas,” with each part having multiple sections. Many of her poems and their titles are in her native Lakota language, and her feature poem “Whereas” is about an encounter she has with a white man in one of her classes while discussing the attempt at an apology Barack Obama issued to the Native population, and the general disregard she and other Indigenous people deal with on a daily basis, never mind the violence. Hers is a sharp analysis, straightforward, unblinking, and very tired. “Whereas in a stirred conflict between settlers and an Indian that night in a circle;/ Whereas I struggle to confess that I didn’t want to explain anything;/ Whereas truthfully I wished most to kick the legs of that man’s chair out from under him;/ Whereas to watch him fall backward legs flailing beer stench across his chest;/ Whereas I pictured it happening in cinematic slow-motion delightful;/ Whereas the curled hand I raised to my mouth was a sign of indecision;/ Whereas I could’ve done it but I didn’t;” (Long Soldier, Whereas).

Her poetry is not without fire, but that you can feel how heavy the burden of this systematic and ongoing oppression is. Long Soldier does not shy away from the reality of what it means to be Indigenous in our world, and she offers her perspective in a beautifully simple prose that is even better when she is speaking it herself.

The poems in WHEREAS are visually very different from so many that I’ve encountered, and no two of them are alike. She structures them each in a unique way that adds to the experience of reading. Your eyes and your book have to move with if you want to keep up, like with her poems “Three,” “Diction,” and “We”:

These poems have forced me to rethink how I go about poetry, how it moves not only lyrically but physically. “Real” poems do not “really” require words. Real poems don’t need to have a traditional shape, or move in a traditional way. They can take you anywhere, and still be poetry.

Long Soldier’s work has changed mine all for the better, inspiring me with her honesty, her simplicity, and her use of structure that challenges the norm. Her poetry stares into the face of a society that wishes to wipe her people from the map entirely, and says “Never.” She echoes the people that came before her while making a place for herself in the world of poetry that is very much her own, and I’m so grateful to be able to experience it.

—Annamae Sax

Share