[insert] Danez Smith (Into the Intersectional Conversation)

Born in St. Paul, Minnesota, Danez Smith earned his BA from the University of Wisconsin – Madison and is currently a MFA candidate at the University of Michigan. In addition to teaching for the non-profit InsideOut Detroit, Smith is a founding member of Dark Noise Collective, a multiracial and multi-genre group of poets/performers exploring themes of intersectional identity, trauma, and healing while challenging the divide between poetic page and stage.

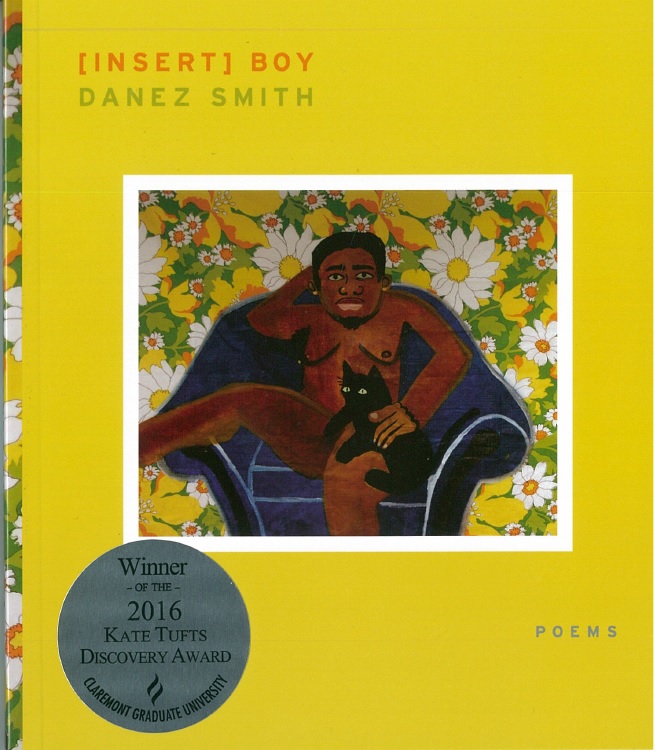

Smith’s swelling list of accomplishments and accolades includes the publication of his 2013 chapbook hands on ya knees, being awarded the 2014 Ruth Lilly-Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellowship and becoming a recipient of the McKnight Foundation Fellowship, winning The Paris-American’s 2014 Reading Series Contest, being featured in Patricia Smith’s The Academy of American Poets’ Emerging Poets series, and placing twice as a finalist in the Individual World Poetry Slam Contest. With the emergence of his debut poetry book, being selected for Claremont Graduate University’s 2016 Kate Tufts Discovery Award can be added to Smith’s already impressive catalogue of achievements.

Danez Smith’s [insert] boy is an unsettling and needed gift. His verses are ripe with beautiful observations, insightful accusations, and chilling lamentations. Smith’s poems are almost corporeal due to their punchy construction and sheer bawdy forcefulness; they leave internal marks upon readers. Partly a contemplation of an African American subcultural past, this raw but elegant poetry collection is also an exploration of the troubled future of black queer America.

Smith confronts the cultural death sentence for African American men head-on. In “Alternate Names for Black Boys,” the poet renames black male youth to reflect their importance and peril. For in his metaphoric reimagining, a black boy becomes both “coal awaiting spark & wind” and the “monster until proven ghost,” the “phoenix who forgets to un-ash” and “what once passed for kindling.” Youthful black masculinity is framed in conflicting terms of triumph and defeat, as a “prayer who learned to bite,” as both “a mother’s joy & clutched breath.” Throughout his collection, the poet rightfully paints African American males as an imperiled yet powerful population.

Yet the poet additionally contemplates queer existence within an African American cultural framework and the resulting intersectional interplay is intriguing. In “Faggot or When the Front Goes Up,” Smith examines the contradictory codes of black masculinity and gay sexuality: “more tomboy than boy. / preferred the dress to the plastic gun. / pined for pink to grace your soft black back.” The poem’s queer subject is consequently reshaped by black heteronormative expectations: “never your grandfather’s boy. / his first words were fist…he called you that word enough / & you turned action figure…a boy made of war. / a boy who swung to keep from singing.” Under the thumb of this patriarchal familial pressure, the once graceful boy becomes a rugged street soldier.

Despite the presence of undeniable queer black despair, hope stubbornly remains in Smith’s work. In “Song of the Wreckage,” the speaker’s queer desire races against inevitable black fate: “I want to kiss these boys…before we are good meat // for some police dog, before we gamble with summer & lose, / gunned down by an almost brother, a play cousin.” The poem’s prayer contains both a gruesome nod to black reality and a queer refusal to accept unquenched defeat: “God / let my small brown lips know their full brown lips before I rot.” In moments, Smith presents black queer love as problematic but not impossible. “I know / what it’s like to be one of the few blacks / for miles,” the speaker admits in “Poem Where I Be & You Just Might.” But he also confesses “I know what our people think / about me, or maybe us.” Yet even amid queer black isolation, there is still the possibility of true connection: “you say / my name like a testimony.” Finally, in “Poem In Which One Black Man Holds Another” the poet presents queer affection beyond mere copulation as a healing agent: “I am learning to touch a man’s back / & not think saddle or conquer or burn…I am learning what loving a man is / not, that we don’t have to end with blood.” Even deeply embedded wounds can be mended and resulting transformations can occur: “I am learning what a brother is / how to touch & not scar.” Here racial and homosexual love blur together into a soothing and restorative balm.

The Kate Tufts Discovery Award was designed to recognize poets of outstanding merit during the early stages of their careers. Danez Smith’s [insert] boy is certainly a worthy recipient: its verses document an unfolding discovery of self and surroundings, captured in a compelling poetic form that demonstrates Smith’s growing lyrical power. It is an intersectional tour-de-force tracing the dualities and commonalities of black and queer realities. Readers cannot help but be humbled by this not-so-humble beginning and will surely count the discovery of Danez Smith’s work as a unique blessing.

—Brock Rustin

Share