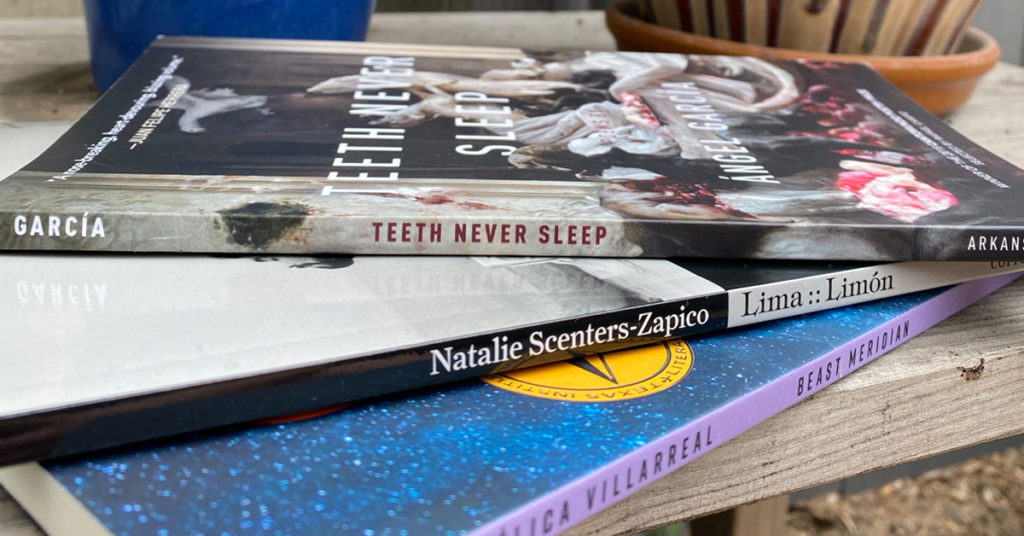

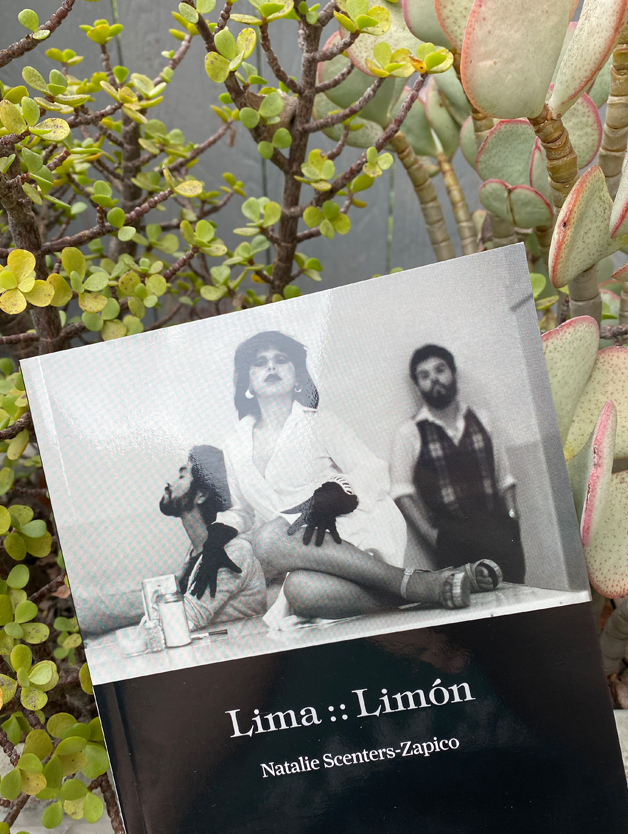

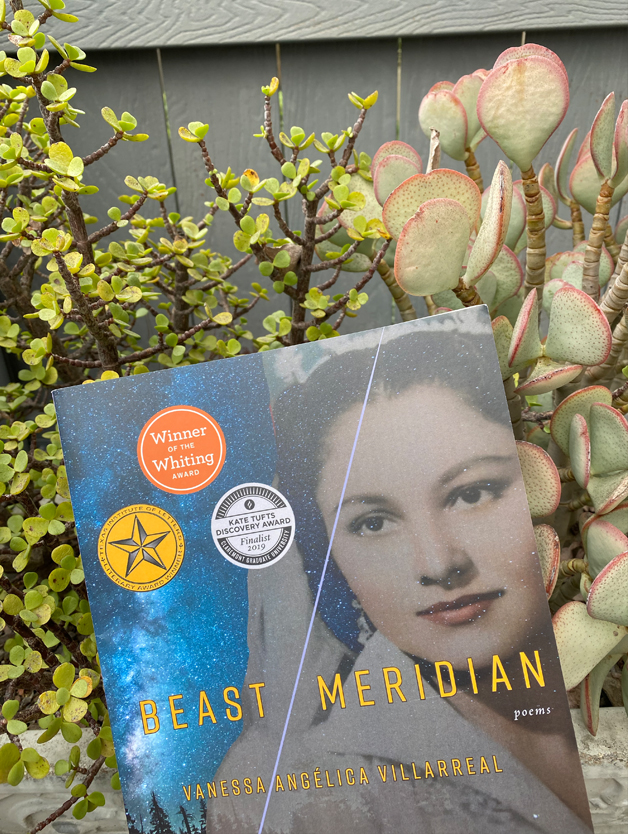

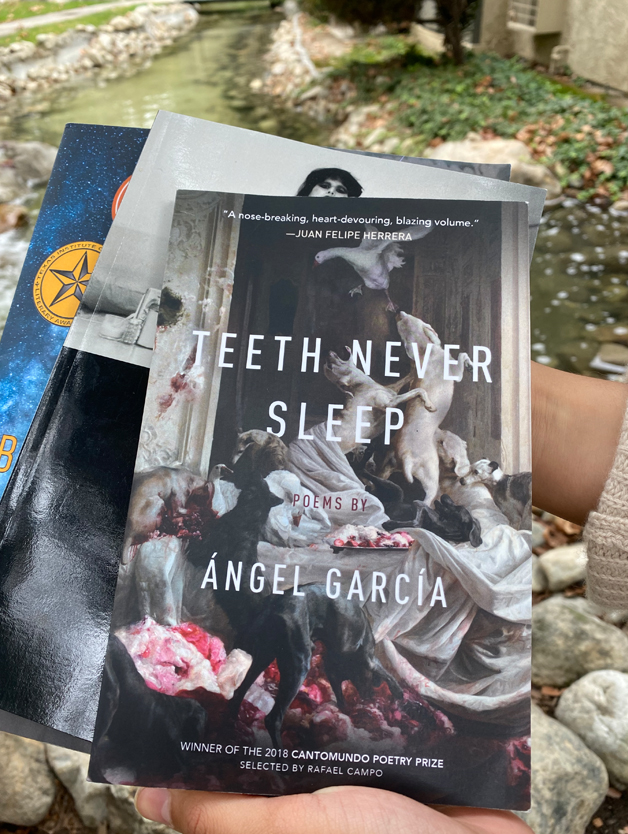

Hispanic Heritage Month Interview Part 3: Natalie Scenters-Zapico, Ángel García, & Vanessa Angélica Villarreal

In the last installment for the Hispanic Heritage Month Interviews, Natalie Scenters-Zapico, Ángel García, and Vanessa Angélica Villarreal discuss technology and craft, influential childhood reads, and the last poem that moved them! Thank you so much for reading this interview series and remember to read diverse writers and poets not just during designated celebratory months!

Lauren Davila: Do you believe the use of technology has helped or hindered your own craft? Do you see it as something beneficial for many people, especially marginalized communities?

Natalie Scenters-Zapico: This is an interesting question because technology can mean lots of things.

If you mean using a computer: I tend to draft by hand, and then move it over to my computer because it slows my writing down. I think more poets should do this because it truly changes your relationship to the line.

If you mean television: I tend to write or grade for two-three hours and then gift myself an episode of a show I like. This keeps me from binging too hard.

If you mean social media: I am trying to use it less frequently. It’s a great resource to amplify the work of others and your own work. But I think we should also be questioning the role the state plays in those spaces and recognize the difference between performances of radicalism and those that are actually doing the often-unseen labor with their immediate communities.

If you mean the email apps on my phone: I need to get better at putting those aside and not answering every email that comes my way the moment I receive it. I am truly a work in progress.

Ángel García: In terms of craft, I must admit technology helps. To be able to work across a page however I want and revise and revise and revise with little restriction and without losing a line or a stanza has definitely been an advantage. To be able to access and find historical and familial documents and then manipulate those documents has become a regular part of my practice. But here, I speak of privilege—the ability to purchase or be “given” access to software by an institution while others go without.

When talking about technology one must also always address access. Who has access and who does not have access to technology? I can’t attest generally about technology being beneficial for marginalized communities, though I must remember that now, like never before, I can and do communicate with family and loved ones from all over the world and similarly, have access to information through the tips of my fingers. It wasn’t always this way, of course. There were very few books in my house growing up. And now, what I can’t afford I can find online. Reading instantaneously at me pleasure. This isn’t the case for everyone.

Vanessa Angélica Villarreal: think poets from marginalized communities are responding to technology and language better than academic or old school poets. I know a bit of coding and back-end server troubleshooting, music notation, as well as graphic design, so poetry was always going to be an audio-visual and technical project for me—a way to rearrange language to mirror my relationship to institutions, to the state, to language barriers and debt and pain. I see so many poets emboldened by this wave of experimentation in queer and trans BIPOC poetry. For example, this poem Cotton Xenomorph recently published, “Misreading” by Anthony Moll uses the HTML drop-down bar for the reader to select their “gender” and then get a poem as their “result.” It’s mind-blowing, and can only truly live and be read online. Lillian Yvonne Bertram’s Travesty Generator and Keith Wilson’s recent work is another example of this innovation. I have an unreleased performance poem I’ve been doing on stage since 2015 that is written in binary and bash code, with sung lyrics in-between. This kind of innovation is only going to grow in the coming years, and I’m beyond excited to see it.

Davila: What is one book every poet should read regarding craft?

Scenters-Zapico: Everyone should read Mary Ruefle’s Madness, Rack, and Honey. Ruefle has such a poet’s mind, even in person. She lives and breathes poetry without exception, and I am so grateful to learn from her in this life.

García: When people ask me, at readings or in classes, what I do in terms of craft, I hesitate to answer those questions because nothing I say about my craft and praxis should become gospel. Richard Hugo wrote something, though this is my poor paraphrasing, stating that everything he taught his students was wrong because he was teaching them, inevitably, to write like Richard Hugo. Though there are plenty of wonderful craft books in the world, craft books can be a strange animal in that they begin to make rules in a poet’s writing life that the poet is then compelled to abide by. This can be extremely limiting for one’s imagination. I would rather poets make their own craft book, meaning that they determine what works best for them and then put that craft into practice.

Villarreal: Craft books are difficult to recommend because many of them are written by and for white poets working within white canons. So I watch a lot of craft talks from Cave Canem and BIPOC poets on Youtube and Soundcloud. Playing in the Dark by Toni Morrison is a balm. Glitter in the Blood by Mindy Nettifee and The Poet’s Companion by Kim Addonizio are excellent. Mostly I get a lot from creative-critical work, too, like the work in Letters to the Future: Black Women, Radical Writing edited by Dawn Lundy Martin and Erica Hunt, Audre Lorde’s writings, and critiques of Ana Mendieta’s work like Radical Virtuosity by Genevieve Hyacinthe. Beyonce’s Homecoming was instructive for me. Discussions of craft are everywhere. We just need to expand our listening.

Davila: What was the most influential book or collection you read as a young adult?

Scenters-Zapico: Probably the works of Federico García Lorca, Pablo Neruda, and Miguel Hernández. They found me when I was carrying so much physical and emotional pain and told me that my pain could have a purpose.

García: This may be cheating, but both books that stand out in my mind are collections. This was the best way for me, as a poor young poet, to get the most for my buck. The collections are Pleasure Dome by Yusef Komunyakaa and Small Hours of the Night by Roque Dalton, which is a selected. Both of these books have been with me the longest and the poems still to this day inspire me.

Villarreal: I’ve always written poetry, but I think it’s the giant collected ee cummings book I bought at sixteen at Half Price Books for $10 that shaped my approach to language as a thing of play, a puzzle, a pliable, flexible thing that can accommodate many utterances, many speakers, many registers in one poem. I loved Caucasia by Danzy Senna in high school, a book I bought on my own, that made me feel possible as a writer, like women of color could write complicated narratives about race in America. Toni Morrison’s Bluest Eye and later Beloved blew open language and narrative possibility for me.

Davila: What was the last poem that moved you?

Scenters-Zapico: The last poem that moved me was Dianely Antigua’s “Anniversary.” She is a poet of deep emotional connections and studies the feminine grotesque in ways that I find open up possibilities in my own work. We should all be studying Antigua’s work.

Villarreal: “Spoiler” by Hala Alyan. “Along the Border” by Jasminne Mendez. “All My Mothers” by Joy Priest.

García: The last poem that moved me deeply was Juan Felipe Herrera’s poem, “breathe we” available on The Academy of American Poets website. It’s a short poem that hurt to read and hurt more to hear read. But we need that hurt, from time to time, to continue living.

—Lauren Davila

Share