Hispanic Heritage Month Interview Part 1: Natalie Scenters-Zapico, Ángel García, & Vanessa Angélica Villarreal

The next couple of blog posts from me will be highlighting and amplifying past Tufts Awards finalists in honor of Hispanic Heritage Month. For those of you who may not be familiar, Hispanic Heritage Month runs from September 15 to October 15. For the purpose of the blog schedule, I may be going a bit past the technical end of the celebration.

Maybe when you look at celebrations for Hispanic Heritage Month, you feel disconnected. Maybe “Hispanic” doesn’t seem like the right word to encompass your specific race, ethnicity, origin. Maybe it’s more difficult to pin down your specific Latinidad. Maybe you don’t fit into the cultural zeitgeist; maybe you don’t speak Spanish or Portuguese. It could be anything, or everything, or something you can’t even explain.

As a Latina writer and academic myself, it can feel alienating to try to explain culture and background–to myself and others. It can feel lonely, as if I am the only person writing from my experience. But as my interviews over the coming weeks will show, we are not alone in writing. There are so many fantastic contemporary poets writing from their own diverse lives and histories and backgrounds. Some of them write within culture; others are writing genre-specific work or historical or in imagined spaces all their own. But diverse writers with voices that explore and invent and reassess are being published every day. We just need to look for them and share their work, not only in months set aside for celebration but always.

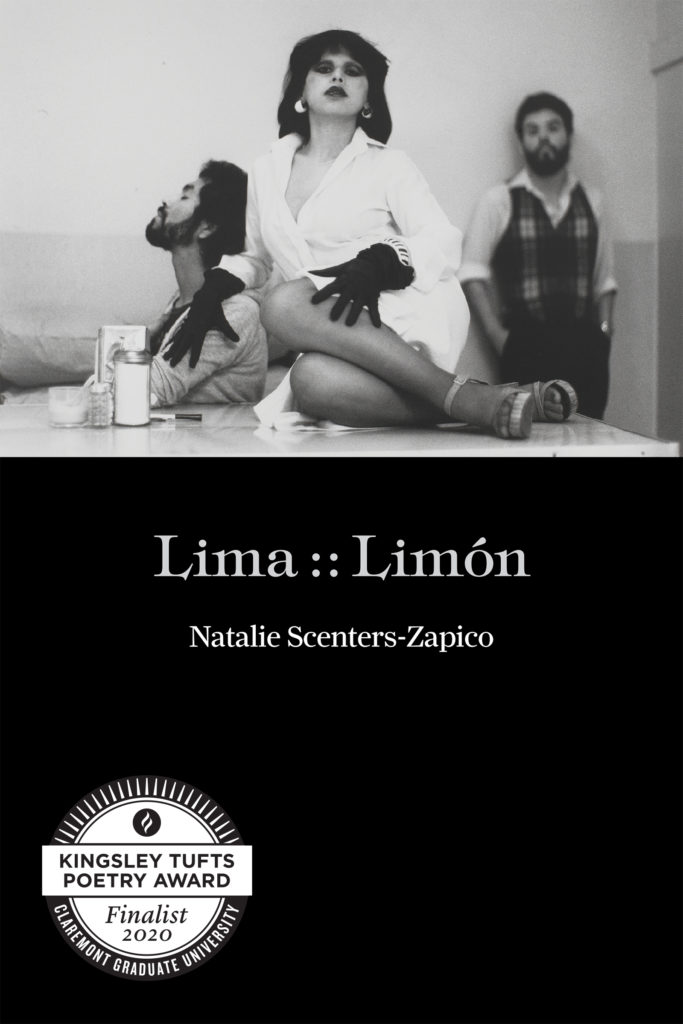

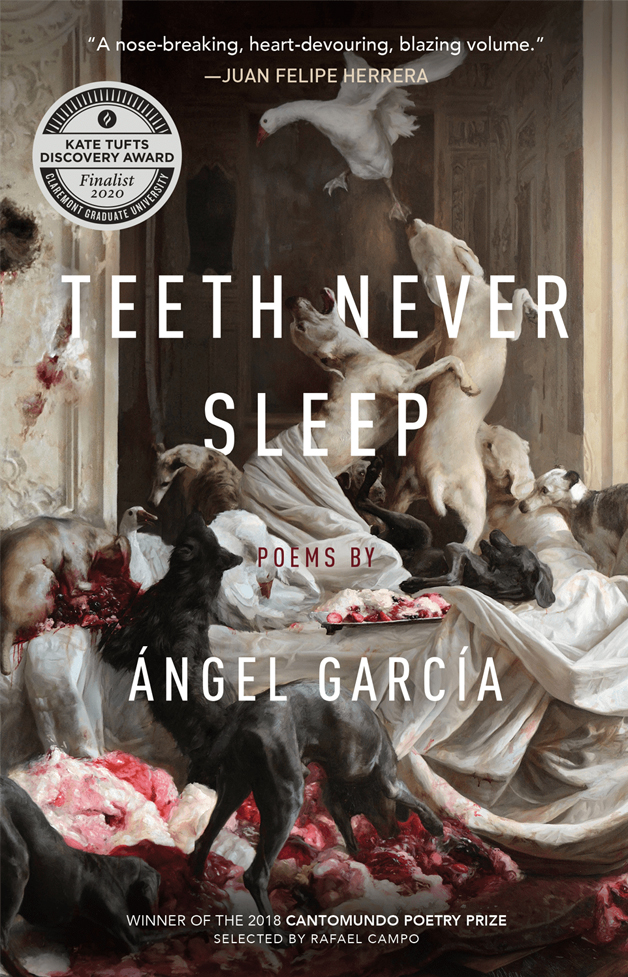

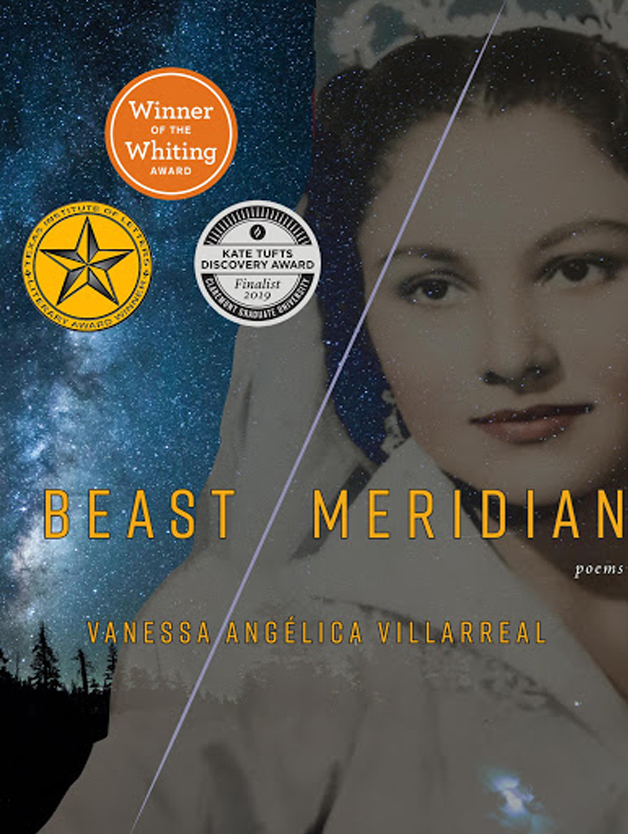

Please enjoy these responses from 2020 Kingsley Tufts finalist Natalie Scenters-Zapico Lima : : Limon (Copper Canyon, 2019), 2019 Kate Tufts finalist Vanessa Angélica Villarreal for Beast Meridian (Noemi Press, 2017), and 2020 Kate Tufts finalist Ángel García Teeth Never Sleep (University of Arkansas Press, 2018). I have been personally inspired by them over the last couple of years and I hope you will find their words encouraging.

Lauren Davila: Please describe your most recent collection or individual publication in your own words.

Natalie Scenters-Zapico: My last book Lima :: Limón is about my relationship to femicide as a young woman who grew up during its height in El Paso-Juárez. I examine how violence against women on one side of the border creates a culture of it for both sides of the border.

Ángel García: Teeth Never Sleep is a collection of poems that explores the emotional theme of grief while also exploring the development and consequences of toxic masculinity.

Vanessa Angélica Villarreal: My most recent collection is Beast Meridian, but that book feels very far away from the work I’m doing now. I wrote that book mostly between 2012-2014 during my MFA when the world looked very different. I was also first-generation everything: first to graduate high school in my family, first to attend college, much less graduate school. I hadn’t read as much as I have now, and had just been introduced to the work of Gloria Anzaldua, of whom I’ve developed serious critiques since. My most recent poem published last year was “f = [(root) (future)],”and is a preview of my current project and its concerns: an erased/erasing past, colonial erasure and the loss of collective and cultural memory, the absence of documents, looking for ancestors in other documents, critiques of time, history, science, and all of the trappings of Western consciousness, spatial thinking, spatializing language.

Davila: What themes or ideas do you find repetitively surfacing in your books or poems?

Scenters-Zapico: I’m obsessed with the violence I survived in my young adulthood and ideas of home. I’m always writing about El Paso-Juárez because those cities raised me.

García: One of the themes that seems to surface most in my work is silence, both on the individual level but also as a learned response to colonization, oppression, and trauma. I am currently exploring the ways in which silence and the consequences of silence have had generational effects on my family in various and complex ways. Family, too, is something that surfaces repeatedly in my work as I try to ascertain and understand patterns of behavior that seems inherited and passed down. Because I am researching and exploring previous generations of my family, I also have to reconcile with the historical events that shaped their lives, and so history, tied to certain regions and certain eras is becoming more prominent in my work.

Villarreal: Mostly a lot of anxiety about disappearing into whiteness, the project of mestizaje and its more pernicious manifestations and intimate colonialisms. Who we desire, and why. Science and medicine as sites of violence. Institutional language as a dehumanizing force. Documents, lack of documents. The memory stored within objects and the land, and how to access that memory in the face of erasure. Motherhood in the wake of histories of sterilization. My mother, my grandmother, my great-grandmother. Who I am missing, and can never remember.

Davila: How does your specific Latinidad influence your writing and yourself as a poet?

Scenters-Zapico: My particular brand of West Texas bilingualism, Spanglish, and my identity as a fronteriza are inextricable from my identity as a poet. I don’t know a poetics without those three things and the experiences that they hold.

García: Because the term Latinidad comes with certain problems, limitations, erasures and makes invisible Indigenous and Afro- Latinx gente, it’s not a term I use often. It doesn’t influence much of what I write in poems. But what it does, even with its inherent problems, is make me want to learn more and do better in terms of my own politics as a poet/political agent in the world. There is so much more I have to learn about Latinx gente and how my privilege has made me complicit in those erasures. The terms, because I see it so often and read it almost daily, serves as a remind to do better and be better in order to do the work that must be done.

Villarreal: This is such a complex question because Latinidad is such a complicated discourse in crisis right now. My specific Latinidad is a borderlands, first-generation, steeped in Texas Blackness, cumbia, and ’90s grunge and indie rock Latinidad. Culturally, I grew up with a cumbiero father experiencing La Onda cumbiera firsthand while living in Houston. But so much about Latinx culture was off-putting to me—its conservatism, its machismo, its whiteness. I felt that hegemony at a young age, wondered at the whiteness of novelas when none of us looked that that in my family. Growing up in the United States, I had a choice not to engage with Latinx media and, like my parents, loved and found solace in Black culture, identified with it, even at times over-identified with it. It was the container for my otherness when no other representations existed, from the Cosby show to Soul Train to Living Single to Poetic Justice, etc. So while my writing is about documentation, creating a corrected record of us, a counternarrative of the violences we survived, I also want to connect it to Blackness and Indigeneity, pay tribute to the artists and scholars who create the spaces I could survive in. I also want to write for those of us who cannot claim Latinidad but exist as other inside the other, racialized outsiders and outcasts, who in a state of ontological stuckness find counterculture as a way to claim space and theorize ourselves into existence, find ways out of our colonial realities.

Davila: What are some of the ups and downs you’ve had in publishing so far? Both in general and as a Latinx person specifically?

Scenters-Zapico: When my first book The Verging Cities (Center for Literary Publishing) came out in Spring 2015, it was mostly read as a book about place. People told me that I was limiting my audience by focusing it so much on my border cities. I got a lot of rejections because my work was read as too particular, and not quite reaching for that which “lasts through time.” We take it for granted now, but when I was coming up, this was a common critique many writers faced. I’m glad that we’re pushing back on such a demand, and in that process opening up space for writers that deserve to be read widely. People also used to roll their eyes a lot at poems that used Spanglish, because they felt performative for a white reader and inauthentic. I use Spanglish throughout my second book Lima :: Limón but try to always prioritize the bilingual reader. I chose which language a line should be in based on the music, instead of the meaning. Like most, journals at times have wanted me to italicize the Spanish, and I’ve always refused.

García: One of the greatest ups of writing and publishing has been connecting with other BIPOC writers and readers. As diverse and heterogeneous as that category is, I feel a strong sense of community with other writers of color as we navigate the challenges of a white publishing industry. And that really, is where the downs live and breathe. It’s disheartening and discouraging to still think about the number of books being published by Latinx writers. It’s offensive to see lines up at readings, names on short and long lists for prizes, mentions and reviews in 2020 still exclude writers of color. While I do believe this is a critical time for BIPOC publishing, and it seems like this might be a renaissance of sorts, that doesn’t necessarily match up with the numbers.

Villarreal: After publishing my book, the reviews and interviews, the invitations, the speaking engagements, the awards—those were highs that I never expected for myself or my work, and will always cherish as proof that, after a long hard road to get here, although late, my work meant something to someone. But even after awards and recognition, I’m still an illegible body. I’m still working alone, unrepresented. It has not been the career boon that everyone said it would be. Degrees are not direct paths either. I am still a difficult, traumatized person making difficult work about difficult subjects that are hard to fit into the discursive spaces of Latinidad, womanhood, queerness, race. I experience far more silence, unreturned emails, and rejections now than early in my career. The spaces I thought would welcome my work are just as inaccessible as before. And I have this feeling, always, that time is running out for me.

—Lauren Davila

Share