Foothill Feature: Diana Arterian

I joined the editorial team of Foothill Poetry Journal during the spring of 2020, and I can now echo a sentiment I’ve heard repeated often both in and outside of our meetings: Foothill is one of my favorite things to do as a graduate student at CGU. Reading graduate-student work from all around the world reminds me of the expansiveness of the poetic process in both space and time. The journal offers a space for graduate students to grow by interacting with one another’s words, both as poets and as editors. I cherish the opportunity to read poets who are in the process of studying their craft, and are at various points in the development of their artistic voice. It offers a constant comfort and a reminder that poetry really is a means to forming a community—there are many of us at any given time who are laboring with words, struggling to find a way to make ourselves heard, to build an apt metaphor, to create a new voice.

As a relatively recent addition to the Foothill team, I benefit from the ability to peruse years of old issues, and to discover a community that has been growing for years and to witness the ways that poets have continued to evolve and create magnificent work in the time since they were published in Foothill as graduate students.

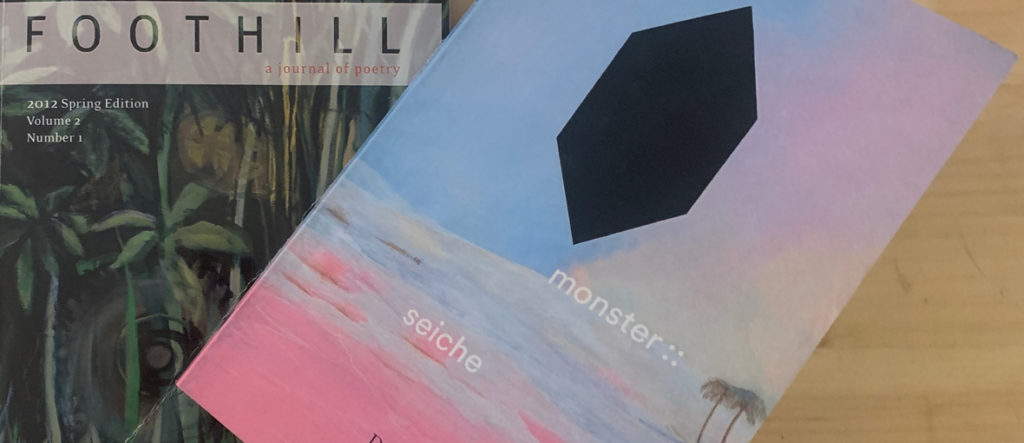

Diana Arterian is one such poet. Her two poems “Last Words of the Dying” and “Last words of the Condemned: On Innocence” were published in the 2012 spring volume of Foothill. These poems, which mirror and twist one another, engage in a conversation between a second person subject with dead poets, thinkers, cultural figures and social actors. These poems offer an early example of Arterian’s ability to sustain a tension and emotion with the objects of her poems as well as with an audience across dimensions, and her capacity to bring the pain and joy of the past into the space of the present.

From “Last Words of the Dying”:

Nothing soothes pain

Like the human touch

I haven’t drunk champagne

In a long time. I have tried

So hard to do right.

Only you understood me

And you got it wrong.

In 2017, five years after her work appeared in Foothill, Arterian published her first book-length poem, Playing Monster :: Seiche. The poem recounts the violence and tumult that can be contained within a singular body—be that body a person, a family, an object—and how that violence moves and spills out into the world across space and time. The poem narrates a childhood with a violent father, and it contains internal turmoil this violence produces in the rest of the family. Moving back and forth in time, the poem enacts the way this trauma travels, like a seiche, unbroken and carried within the body of the family. Even if when the family dissolves, when the speaker escapes the violence, the poem still protracts the past, showing how trauma sustains violence in the present.

Grounding the poem is the metaphor of a seiche, which Arterian defines within the first few pages of the text:

A phenomenon that occurs within a confined body of water such as a lake, sea, or pool. Once disturbed, the enclosed water may produce a “seiche” or standing wave that moves across the surface or, when below, between the warmer upper and colder lower layers. The wave does not break (6).

The poems, too, move through across surfaces and amongst layers. Woven from two temporalities, Playing Monster brings us into past childhood traumas and violence, while Seiche pulls those past events into a more recent time in which the childhood chaos ripples into the speaker’s mother’s encounters with violent men. The violence of the past and present, traumas of the father and mother, converging in the speaker’s present, fear and love roiling in and around her:

We sit close our eyes

feel fire-oven heat olive leaves

our then-threat of my father real but known (152).

Looming over the past and the present is an unknown and unknowable monster. The poem’s movements seem to attempt to root out the mysterious source of fear and cruelty, but also approaches the monster with startlingly gentle verse, capturing the disorienting reality of the dangerous love of an abusive parent, and the fatigue of anger, and the impossibility of complete escape:

“My father apologizes”

He mends his small holes

near the collar of my shirt

Violence is at the heart of it

A sure hand all its capacity

Violence whistles sparks The hand

clawing windfire

To experience the feeling of Arterian’s text, you can watch and listen to this book trailer she created, which visualizes the way the poem creates a place, destroys and returns to that place again and again.

I’m proud and grateful to be connected to books and poets like these through the shared space of Foothill. Placed along a gradual increase in elevation at the base of the hills and mountains of the Los Angeles National Forest, CGU’s in-house poetry journal positions itself as something of a base-camp for emerging poets: offering a place along the way to gather one’s rations and hone one’s skills for the more uncertain and perhaps daunting terrain ahead. It creates a place to meet, confer with and learn from other travelers, creating tenuous but resilient and affirming connections among the vast community of people who love to venture out into the world of language.

—Lilly Fisher

P.S.: Listen to Arterian talk about centos and read her poems here.

Share