Encountering Poetry Through Images

I’m an initiate to poetry. I’ve had dalliances with the genre in previous lives, but I had never invested myself into it the way many of my colleagues and friends have at CGU. I am a critic informed by the radical aesthetics of the 1980s and 1990s comic-book culture and their Saturday morning cartoon cousins. A millennial who was taught how to deductively and inductively reason under pressure through the multimodal immersion of video-games. In other words, I have always been and still am a so-called “visual learner.” So, when I first came to Claremont last year for graduate school looking to get involved I was excited yet slightly apprehensive to join the poetry community here. Yet still, I was intensely interested in developing my critical skills with any and all forms and mediums. At the encouragement of many of Foothill’s editors, I leapt into poetry headfirst. Foothill likes to cultivate a cadre of diverse minds and voices, and because I am the only Cultural Studies and Media Studies student on the team, I’m able to lend my perspective where and when I can and contribute to that diversity. But, I still felt that I needed a crash course in poetry on my own terms.

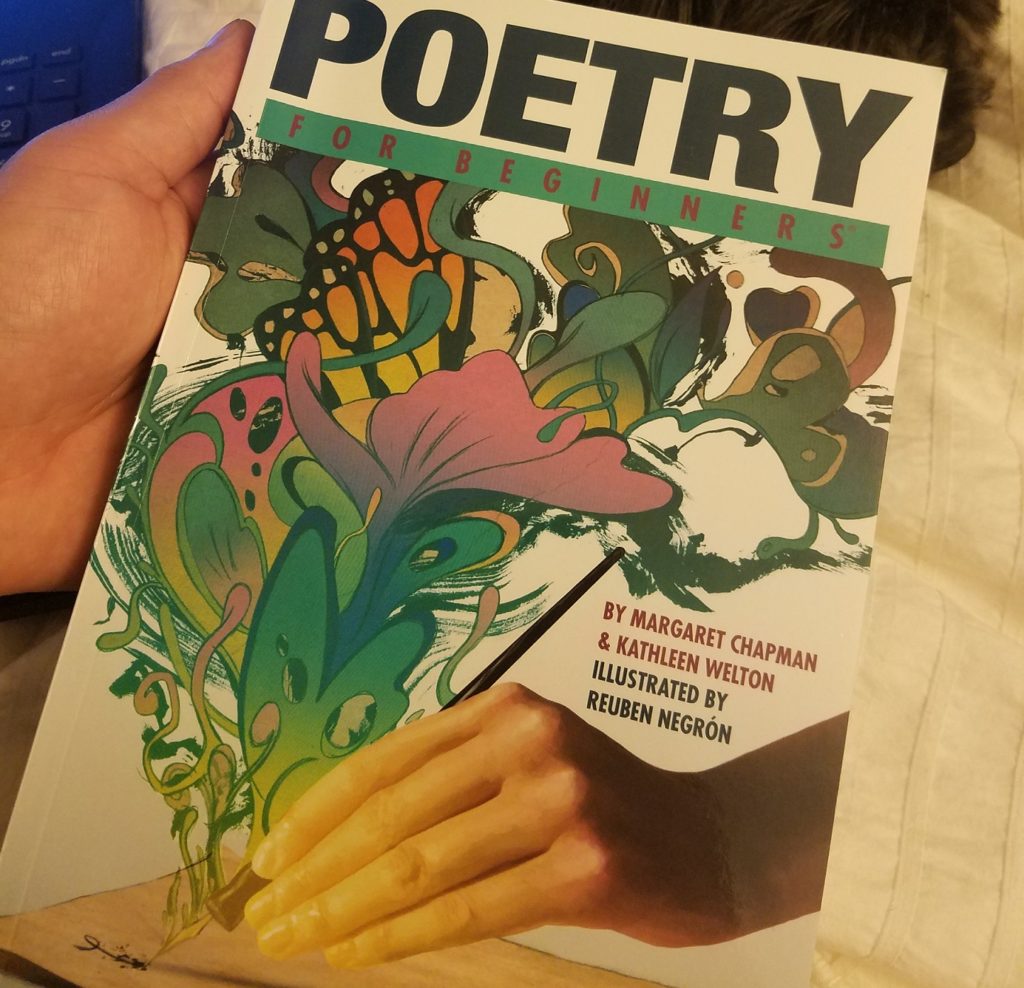

I scoured online sources for introductory guides to poetry and eventually came upon a guide that piqued my interest: Poetry for Beginners. Previously, I had read other nonfiction “educational” comic-books such as Freud for Beginners and Marx for Beginners in upper division undergraduate courses. The visual approach that deploys the comic form while simultaneously grappling with and explicating information was and still is, fascinating to me. I picked up a copy of Poetry for Beginners and began to learn.

The 151-page book situates its ideas into five different sections. The first section outlines questions like “what is poetry?” and attempts to give the many ways in which people have defined the boundaries of poetry. The second section explores how one can understand a poem through the various textures poems can have or embody. Sections three through five give historical overviews, genre classifications, and ultimately how to begin writing your own poetry. For most of you reading this I think it is safe to assume that a book such as Poetry for Beginners can feel superfluous or unuseful. The book’s intended audience seems to be the general public with little to no experience with poetry. However, I think it’s important to revisit and explore familiar objects through new means and forms.

One section that struck a chord with me was the “Post-Modern Poets” pages that dealt with Black artists, hip-hop, and spoken word. My cultural studies sensibilities were ringing as I read about the controversy hip-hop had caused in poetry in the late twentieth century during its initial rise into mass culture. The section even goes as far as to claim a position in the debate regarding hip-hop and its classification as poetry. For the book’s writers, hip-hop IS poetry despite its flirtation with the fine line that separates song and spoken word. Inclusions like this serve to democratize the genre of poetry while simultaneously acknowledging and validating the work of Black artists. With that being said, “Post-Modern Poets” falls short by relegating Chicanx, Feminist, Indigenous, and Post-Colonial poetry to a footnote. They could’ve done better.

Despite the book’s shortcomings, I think there’s something to be said for juxtaposing images and poems. Poetry for Beginners isn’t a book that has created images in conjunction with poets; rather, it is a book that provides images to support the existence and history of poetry. Nonetheless, whether you’re a seasoned poetry veteran or an initiate like myself you can benefit from reading Poetry for Beginners. Because unlike the title suggests, the book is really for everyone—for those who are interested in newer forms or those who just want a second glance.

—Jamey Keeton

Share