Encountering Newness through Poetry

I planned to use my first blog post to introduce myself and explain my relationship with poetry, but I have found both of these tasks challenging to complete for similar reasons. The past six months have seen both stasis and upheaval, institutional collapse and collective demand for a different future. The foreclosure upon things we have come to take for granted—a hug from a friend, a handshake from a stranger, breathable air—have, I think, also allowed us to consider what else we assume will always be the same, but could be different, could be better. The past six months have changed a lot of things, and they have changed me. And during this time, poetry is allowing me both to escape the present and to be more tangibly in the present. Poetry can do so many things—it can make us feel seen, it can let us to see others; it can give us a new way to look at the world; it can give us a new world to look at.

Adrienne Rich wrote the poem “Natural Resources” in 1978, but its last six lines are often cited in times of turmoil and grief. She expresses a sentiment that feels at home in any time of simultaneous mourning and survival:

My heart is moved by all I cannot save:

so much has been destroyed

I have to cast my lot with those

who age after age, perversely,

with no extraordinary power,

reconstitute the world.

This poem, and this excerpt in particular, asks: what do we with our despair? How, in the midst of crisis, can we build something new? Rich attends to devastation not to move on to something else, but asks how we imagine a different world, in spite of our heartbreak. Who can we turn to show us what to do with our grief and our joy? Certainly, some of those people who again and again, age after age, work to reconstitute the world, are poets. Poiesis: “the activity in which a person brings something into being that did not exist before.” Poets take materials of the world: our shared histories, and our mutable languages, our natural resources, in other words; and again and again, age after age, try to create something new—a way of looking at a blackbird, a way to see without seeing, a way to rewrite history.

In this moment full of unprecedented events, I think we could use some help finding new ways to look at this changing world. Excerpted from various emails I’ve received from corporations, campaigns, organizational mailing lists: we are living in “difficult, uncertain, scary and extraordinary” times. I have felt every inch of these adjectives; indeed, some days, the oscillation between difficulty, uncertainty, fear, and strangeness seems to mark time better than hours in the day. In this period of staying in an apartment, wading through disambiguated time, it can be hard to find novelty even as the world around us feels so unfamiliar. And yet, the sensation of doing, seeing, feeling something new is crucial to allowing ourselves to grow, and moreover, to change the conditions around us. Luckily, there are always poets making new things, bringing newness into the world.

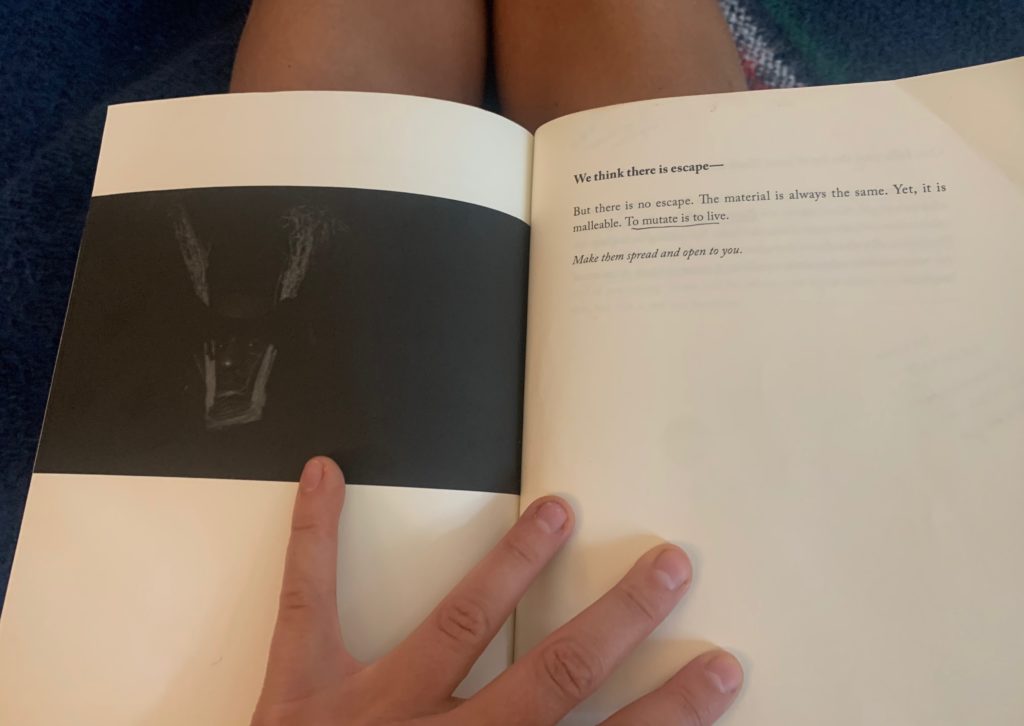

The Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award is given to a mid-career poet, but the award has introduced me to many brilliant poets for the first time, and these poets offer me new ways of looking at the world. Last year, I was lucky to be meet Dawn Lundy Martin in person and through her writing. Returning to Good Stock Strange Blood many times since last year, I see it anew every time. Preoccupied with the question of building something new in the midst of catastrophe, I am struck by a small poem that speaks to of confinement and transformation:

We think there is escape—

But there is no escape. The material is always the same. Yet, it is malleable. To mutate is to live.

Following Martin brings new words, phrases, feelings into my world. She continues to give us space to move outside of ourselves to look at what may be happening around us and to us, whether or not that what we see will make any sense, as in Perspective is Supposed to Yield Clarity.

I also encountered the 2020 Kingsley Tufts Award winner Ariana Reines because of the Tufts Prize, and through her work I have been introduced to new ways to think about movement and communication. Reines’s poems, although full of historic and mythical themes and references, feel like tools to help us understand the present. Reines’s startlingly insightful poem “A Partial History” explores the effect that cultural communication through social media has on our collective understanding, our personal subjectivity, and the future these effects may bring:

The images gave us no rest yet failed over

And over despite the immensity

Of their realism to describe the world as we really

Knew it, and worse, as it knew us

Reading how Reines explores how the Internet affects our personal and collective consciousness, more questions about our present moment emerge. As we have to be more cautious of our proximity to other bodies, as we are forced to mourn murders and preventable deaths in isolation, as those of us on the West Coast look out our windows at a brownish, hazy sky and an angry red sun, what is happening to our minds? I am grateful to Reines for her standpoint and her efforts, which allow me to consider these questions that are new, to me.

Share