Building New Traditions: A Conversation with Vanessa Angélica Villarreal

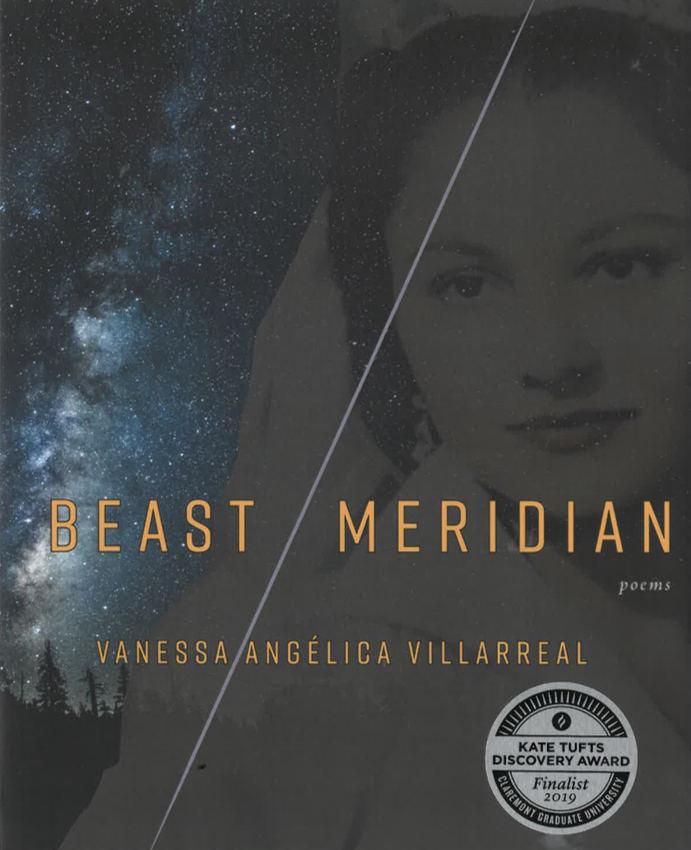

I had the honor of talking with Vanessa Angélica Villarreal, the author of Beast Meridian (2019 Kate Tufts Discovery Award finalist). I was buzzing with joy after our conversation because it became so clear to me that her power as a poet stems from her genuine and uncompromising voice. We talked about her background, writing trauma, finding freedom, and building new traditions—I hope you enjoy her words as much as I did.

SP: Beast Meridian is full of exciting form. How do you view the relationship between form & content in poetry? What informs your choices re: form?

VV: When I started studying poetry more formally, I was frustrated with the limitations of certain received forms, even free verse or blank verse, because the sonic qualities and visual potential of the language weren’t achieving enough in a left justified poem on the page. Having a visual art and photography background, I wanted poems to use the field of the page to visually open up the potential for multiple readings, or show up as disciplinary forms, prayer cards, windows. I entered my MFA program as a fiction candidate, but I was frustrated with prose because I didn’t really care about linear plot. I was more fascinated with the moment in sentences and lyricism. But the poets were very anti-lyric, anti-narrative, anti-“I.” I wanted to write both genres, rebel a bit against the very white, very limited definitions of experimentation my program was pushing. My mentor in the program, Ruth Ellen Kocher, thought similarly about this. Through her classes and guidance, I found permission to not write a poem “properly” and to experiment. We often talked about the concept of “mastery” and the deformation of “received” forms, and how writers of color are often not given permission to be “masters” of these colonial forms. So we deform them. And the idea of deformation was so powerful, and it unlocked something for me—I remember my grandmother’s long scars on her body, how I had bad and missing teeth growing up—the physicality of deformity speaks to me. Deforming language allows me to work through trauma.

Does embracing deformation/deformity in your poetics have a connection to a Chicanx tradition?

I didn’t read Chicanx literature growing up in Texas, or know the history of the tradition, until I moved to LA. In my undergrad classes, no one taught Chicanx or Latinx authors except maybe one Cisneros story; the only way you could read them was in a language and cultures class. It was considered “niche.” I only read British or American writers in my literature classes and workshops. There was still a stigma that prohibited the recognition of Chicanx or Latinx work as “real” literature.

So when people identify my book as Chicanx, I feel honored, but like an impostor. Mexican people don’t really identify as “Chicanx” in Texas other than academics, and college students don’t encounter Chicanx or Latinx writing unless they explicitly take the courses, which are often daytime, MWF classes and not accessible to working people. The inspiration for my book came mostly from ‘90s music—grunge, cumbia, jazz, R&B—and writers like Douglas Kearney and Jennifer Tamayo. The book was born of wild experimentation out of a sense of estrangement from American poetics that I didn’t feel accepted or well-versed in. Because I didn’t really read a lot of Chicanx authors in college, a lot of these authors are still new to me, which is another kind of shame and estrangement from my own community. I’m learning and creating in this tradition at the same time.

Can you talk about how your latest poem, “f=[(root)(future)]” in Poetry Magazine was born?

Postcolonial theory and memory studies are central to my research, specifically the erasures of colonial intimacy and gender violence in the archive, and how to redefine cultural memory and reclaim history as it fades. For instance, I found this archive of marriages in northern Mexico and the borderlands, but I couldn’t find my grandmother. I couldn’t find her birth, marriage, or death certificates. I looked for other family members by surnames and I didn’t recognize anyone—not even my great-grandmother Carmen, and I know she existed. I buried her. But in the record, she doesn’t exist. I’m going to be the only one who remembers her after my mother passes, and my great-grandmother is one of the last connections that I have to our indigenous lineage. So I have all this archival anxiety and anxiety around the loss of memory.

I was also on a panel with Morgan Parker and Kimiko Hahn called “Women of Color Write the Future.” We were commissioned to write a poem for the future, which felt so impossible—the future is not guaranteed to us. Capitalism has so ravaged the earth and makes it so hard to eat and pay rent and survive. Precarity is the norm. We’re careening into the apocalypse that capitalism, that cis white men, have created. So it made sense: if white men have pushed us to the end of the world, then womxn of color can save us, imagine a possible future. So I wanted to illustrate how I see the progression of ‘real time,’ this idea of the Western version of history beginning at the time of conquest. The official record doesn’t start until the point of colonial encounter—the world itself is arranged from the European perspective, from the Prime Meridian. People of European lineage can trace their family trees back into 1600s, have family crests. That grip on history, that hold on the world’s story and narrative—who gets discarded and who gets remembered? So I wanted to replot linear time, visually illustrate lost lineages, the silences of intimate violence, conquest, domination, destruction using set theory and math, these patriarchal and logical grammars. But ultimately, this is a poem for my son. We can keep going on the path to apocalypse, but our children will carry all this, and deserve more, deserve for us to go back.

How have you changed (or stayed the same) as a writer since writing Beast Meridian?

I was very self-conscious and had a deep sense of imposter syndrome while writing Beast Meridian during my MFA. I didn’t know what I was doing and I didn’t know who anybody on the syllabus was. I was always trying to fit in but failing, constantly reliving the trauma of rejection and ostracization as a Mexican-American, first-generation, working class woman of color. So the book went back into traumatic memory, but was marked by a lot of self-silencing and self-censorship, despite the vulnerability on the page. I look back at that poet and I had so many more radical directions and ideas that I wanted to explore. But I’m also proud of the risks I did take.

I’m most excited about the growth from that place of deep insecurity to now having faith in my work and my vision. I don’t feel as much shame about lacking a traditional canonical literacy because that’s true to my working-class identity, my race, my struggle—it’s part of who I am and where I come from. I’m glad to be forging my own space on my own terms, to give others permission to do the same, no matter who you are or where you come from.

—Stacey Park

—

Vanessa Angélica Villarreal is the author of Beast Meridian (Noemi Press, 2017), a recipient of a 2019 Whiting Award, a 2018 Texas Institute of Letters Poetry Prize, and a 2019 Kate Tufts Discovery Award finalist. She lives in Los Angeles with her son and a loyal dog.

Visit her website to learn more about her work.

Share