Against Art Tyrannies: Thoughts on What’s Happened with the Poetry Foundation

If you haven’t been following the events surrounding the Poetry Foundation in recent weeks, I’d read this and this before reading this post.

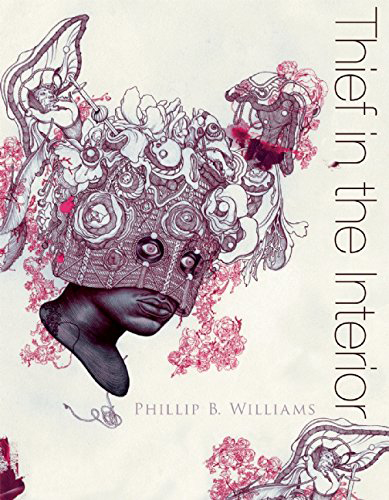

As I witnessed these events and actions unfold, I listened to what many poets I admire had to say. I was incredibly moved by Phillip B. Williams, a previous winner of the Kate Tufts Discovery Award, and his Letter of Apology from a Ruth Lilly Fellow. It contains nuanced, honest, and bold expressions of complicity, disappointment, and personal accountability in light of the double bind that many traditionally marginalized poets are placed in when patriarchal, white systems reward them.

There are several takeaways I’ve gleaned from what I’m calling “Poetrygate,” but one is most exceedingly clear: I am against tyrannies in art, against how the ways of big business have corrupted how we value and accept art.

Poetry is not a lucrative business, nor is it really popular in the greater literary landscape—no one is doling out six or seven figure checks for poetry manuscripts (at least none that I know of), and no one is turning poetry book deals into movie deals (though I’d love to see a movie inspired by a poetry manuscript). In our current system, there are only a handful of institutions that have devoted the big bucks to support poets and poetry, and, therefore, have become the arbiters of approval.

Getting published in Poetry Magazine, becoming a Ruth Lilly fellow, or winning a Kingsley/Kate Tufts Poetry Award are like getting a proverbial blue check mark in the world of poetry. These awards, getting published and recognized in these ways, are major benchmarks of “making it.” And not only have they made it, they are in—invited into the upper echelons of literary circles and institutions that have major influence on poetry and its culture.

This sort of self-serving cycle is what Williams calls out in his letter, and what many have historically criticized about how art operates in a capitalist society. And I think this is how tyrannies are formed in art. Williams asks how innocence can exist in the “age of an empire”? And I have similar concerns—literary success is increasingly dependent upon who grants, approves, and funds that said success.

It is even more insidious when these institutions are run primarily by white, male, “prominent” figures, who are patted on the back for these shows of diversity and “care” for marginalized authors. On the surface, it’s easy to say, “they’re not bad, look at what they’ve done for [insert community],” but there is an inherent, imbalance of power in a relationship between a white editor and a marginalized author. The author’s work is still overshadowed by what the editor does, what the magazine did for the author. Authors are expected to be grateful and to cooperate with this system that’s paid them, and the author’s credibility and their work is forever tied to the editor/organization. This is how an organization performs smoke and mirrors to be seen as a benevolent, “giver of opportunity.”

I am guilty of prizing this system—of looking to Poetry Magazine to read the poets I “should” be aware of, and thinking “wow, how lucky are they, how chosen are they” to have been published in Poetry. Singular institutions cannot have that much power, that much influence.

When poems become commodities and poets become workers, art becomes the plaything of white plutocracy. I want to move toward a system where resources are not hoarded by the few, but where art and artists can be celebrated and showcased in numerous, new, and unimagined ways—in ways where reward and recognition are not contingent upon the wealth of organizations.

I am trying to divest from art tyrannies while thinking about how writers can have their basic needs met while having the time and space to create, how poetry can live and thrive in my immediate community, how to undo the ways poetry has been coopted to become a divisive means used to maintain the borders between the “haves and have nots.”

I have no concrete answers yet, and I may never arrive at anything conclusive in the near future, but I am questioning. I am encouraged by those in the poetry community who continually interrogate the spaces and systems that distract them from who they are and what they do: poets, who write damn good poems.

—Stacey Park

Share