“A Music Made of Visual Thoughts”: The Home School Reading and the Power of Listening

In a piece of short prose titled “Modern Poetry,” the poet Mina Loy writes, “More than to read poetry we must listen to poetry.” Before praising the work of her contemporary poets like Ezra Pound and e. e. cummings, her essay discusses poetry in the shadow of American jazz—two musical forms, the one preferred over the other. Poetry, she declares, is “a music made of visual thoughts, the sound of an idea.” Earlier this month, one poetry reading in particular had me thinking about Loy’s charge to listen to poetry.

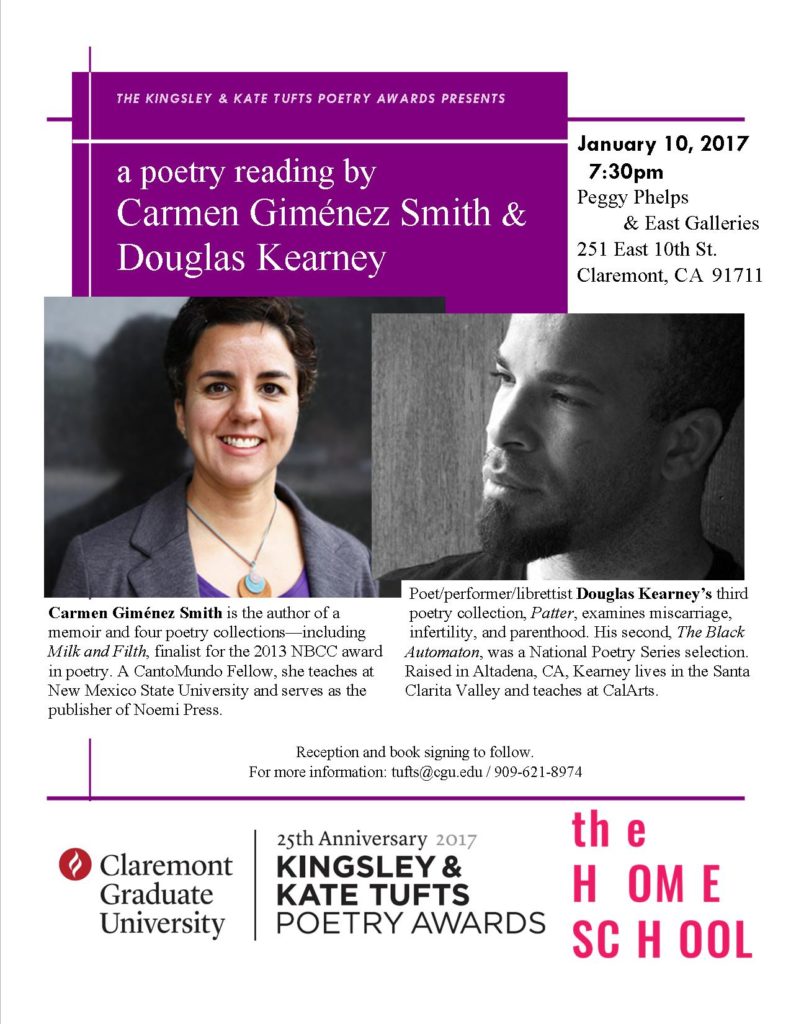

On a rainy Tuesday night before Claremont’s campuses had resumed after winter break, the Home School (with the help of the Kingsley and Kate Tufts Poetry Awards and some of the Claremont community) overflowed the Peggy Phelps & East Galleries with a reading that first filled the room with people and then with the musical cadence of its poetry. The room was pressed for space but with no shortage of quality acoustics. The invited poets, Carmen Giménez Smith and Douglas Kearney, read published, unpublished, and soon-to-be-published work before the crammed yet attentive bodies, charming the room with their powerful and distinct poetic melodies.

The first of the two readers, Carmen Giménez Smith, began with a reading from her recent publication Milk and Filth (The University of Arizona Press, 2014)—which sold out within minutes after the reading. But perhaps the most memorable and certainly the most musical element of her reading was in her final poem: a beautifully rhythmic, spoken word poem soon to be published by Graywolf. Giménez Smith began this final poem with an explanation of her relationship to its oral presentation—that every time she reads the poem she can feel herself better at pronouncing it. The poem itself is a response or a tribute to Pedro Pietri’s “Puerto Rican Obituary” and it presents itself in a series of questions which defy the rules that Giménez Smith previously had against questions in poetry. Playfully and profoundly the questions in this poem build upon each other, touching on relevant personal and political issues, and crescendo-ing, if you will, in both content and oral presentation.

Following Giménez Smith, Douglas Kearney read multiple poems both published and not. For those familiar with his work, it is unnecessary to describe how and why his reading led me to think about the relationship between music and poetry. His poetry is as musically experimental as any avant-garde jazz band; and the range and diversity of sounds, volumes, and tempos enriched the already musical themes of the poetry’s content. Beyond shout outs to Marvin Gaye and Janelle Monae, Kearney shared with us two poems he had written after Prince died in April 2016. Both poems—”Controversy” and “When Doves Cry” —incorporated ideas from the music videos and the music from the early 1980’s, recapitulating the artistic range of Prince himself. Kearney’s reading challenged many notions of “ordinary” poetry readings, and instead acknowledged and expanded his poetry’s own musical potential.

Of course, the musical qualities of poetry do not only belong to the spoken word poets and the musically inclined. Instead, as Loy sees it, the meter of poetry reflects any poet’s way of life. This, she says, is poetry’s secret: “It is the direct response of the poet’s mind to the modern world of varieties in which he finds himself.” That is, the cadence of poetry when listened to tells as much about the life of the poet as the content ever could—it simply takes the poet’s voice to help the musicality of the work reach your ears.

—Ashley Call

Share