The Poems in My Blood

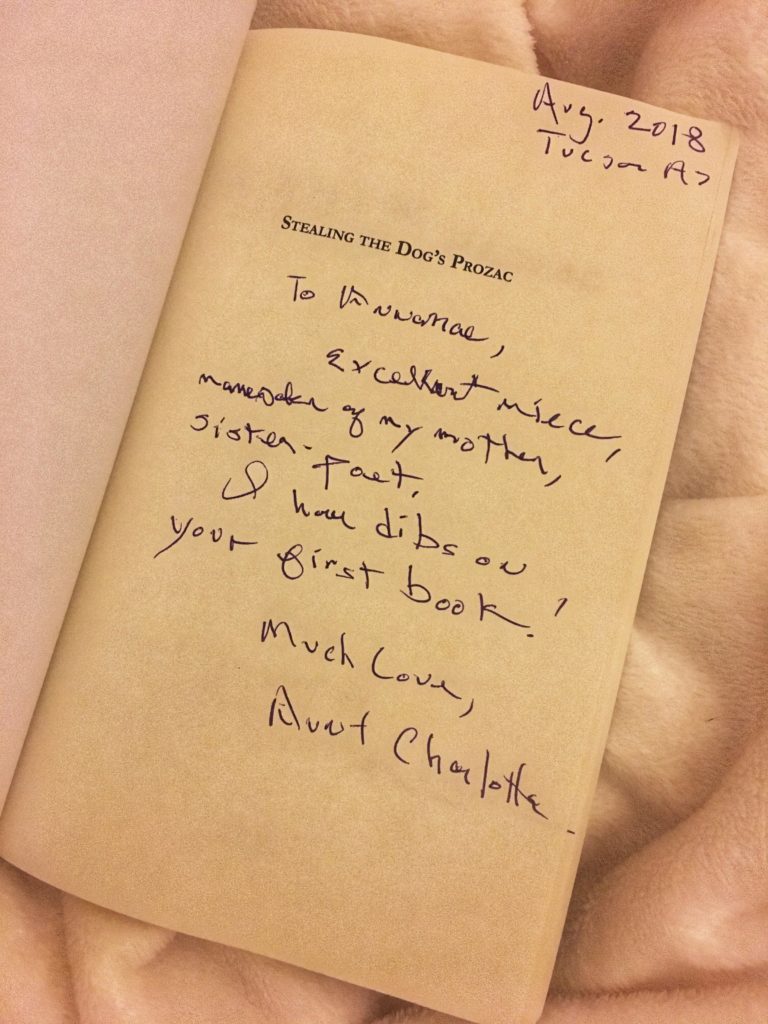

“To Annamae,

Excellent niece, namesake of my mother, sister-poet.

I have dibs on your first book!

Much love, Aunt Charlotte.”

August 2018, Tucson, AZ.

Scribbled in jet black ink, a scrawling eager hand, this is the inscription on my copy of Stealing the Dog’s Prozac, poems by Charlotte Lowe. It’s a sharp little book, packing a fluid punch that is unafraid and gasping.

Charlotte Lowe is my aunt, my mother’s oldest sister, and the first poet I ever encountered. Growing up in the dirt and cactus of Tucson, Arizona left me sun-browned and angry with a poet’s voice to match. When I was little and just starting to write my way out of my frustrations, Charlotte existed on the horizon, a sort of ethereal being that held the coveted title, author. She was blonde and blunt and almost scared me, how badly I wanted to go where she was going. Then I got older, and where there was intimidation, just this past summer there appeared kinship. Our similarities are so clear, even my mother jokes about them, and my younger self would jump for joy to hear our conversations, or perhaps shiver at the secrets unfolded by two writers.

I was my aunt’s personal assistant this past summer, saving up money to move from Arizona to California for graduate school, and my assignments varied from sorting out her writing, to organizing the artwork of three generations of Claude Bailey’s in the family to go to gallery, to reorganizing the large card rack of ancient black and white photographs from three to four generations back of our family. I learned so much this past summer, about my mother’s side of the family that moved down from Ireland to the South, about my aunt and my mother growing up together, and about poetry. My favorite conversation we had took place in her car, the charcoal grey toaster, as it climbed over the baking hills of her desert Tucson neighborhood. We discussed the danger of being a writer, and of loving a writer. I had an Irish professor once say to me, in our creative writing workshop, that everything was free game to a writer. We write what we know, and our experiences offer inspiration. It had gotten him in trouble with his wife more than once. I shared this with Charlotte, and she said it was true, and that she had learned to strike a balance.

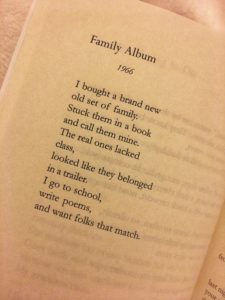

In Prozac, there’s a poem titled “Family Album” where the speaker wants “a brand new/ old set of family” because “The real ones lacked/ class” that Charlotte told me she read out loud at an event her mother, my grandmother, was at.

Aunt Charlotte recalled that her mother came up to her after, absolutely delighted by the reading and so proud of her and her writing. Charlotte said she feels bad about it to this day, and it makes me think of my mother’s frustration about the writing I was turning into my teachers in high school, and how my fearlessness about my complicated family felt like airing out our dirty laundry to her. I’m learning the balance Charlotte has learned, the line to walk between my own truth and honoring my family.

As I piece together my first book of poetry, written about and for my brother Tyler, I continue to find the same violent, varnished silver and turquoise streak in my Aunt’s and my writing. An honesty about our history, truth and acceptance for our imperfect families, and bravery in the face of trauma and loss. There’s an absence of sugar coating and hesitation; we have something to say, and our poems say it.

In “Ghost Pass Through,” Charlotte writes about the day her mom, my grandmother Annamae, died and how they danced through the night to help her pass on. For my eccentric grandmother, dying of cancer, Charlotte writes, “You are a fiddle screaming/ across the night./ Ghost, when will you leave this life/ filled with too little of you/ left to love?/ Be a good mother,/ take the night,/ pull it tight under my chin./ Ghost/ pass through” (pg 25). My beautiful Aunt, bad blonde, lucky blonde, who has taught me how to find a poem in my grief since I was little.

—Annamae Sax

Share