Unfolding/Rebuilding: Literary Emancipation in Tyehimba Jess’s Olio

A dictionary entry; a five-page table of contents; an “Introduction / or / Cast / or / Owners of This Olio”—these are the materials that situate readers in Tyehimba Jess‘s Olio. As the winner of the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry (and a 2017 Kingsley Tufts finalist), Olio is a masterful blend of genres that tell an old, neglected story in a new, experimental form.

But Jess’s blend of literary genres (indeed there is poetry, prose, drama, as well as letters, drawings, and large fold-out pages) is not for the sake of the poetry itself but for the history of which the book is representative. The book engages multiple meanings of the word ‘olio,’ one of which is “the second part of a minstrel show which featured a variety of performance acts and later evolved into vaudeville.” In this poetic performance, Olio seeks to expand the deep and human history of pre-Harlem Renaissance black musicians and performers whose stories were once flattened for the entertainment of a white audience. The multi-genre form is one way in which Jess is providing a literary emancipation for this generation.

Beyond genre, Jess deploys numerous techniques to conduct an un-folding, or rebuilding, of the lives behind the minstrel caricatures. The expansion of the artist’s stories occurs in both the content and form of Olio. Performers tell their stories through interviews, and the syncopated sonnets allow these performers to speak back to their stories (e.g. when “Henry ‘Box’ Brown blackens the voice of poet Mr. John Berryman’s ‘Henry’…and liberates him[self] from literary bondage!” [71]). As Jess gives a contemporary voice to these individuals, he challenges the dominant discourse of their lives and memories that has led to their neglect in the larger American narrative. And he seeks to emancipate their histories.

Still, Olio‘s full narrative relies upon the imagination and active participation of the reader. From the introduction, the reader is encouraged: “Fix your eyes on the flex of these first-generation-freed voices: / They coalesce in counterpoint, name nemeses, summon tongue to wit-ness / Weave your own chosen way between these voices…” (3). As is stated here, and elsewhere, readers of Olio are actively called upon to engage with the variety of the text’s content, voices, and form.

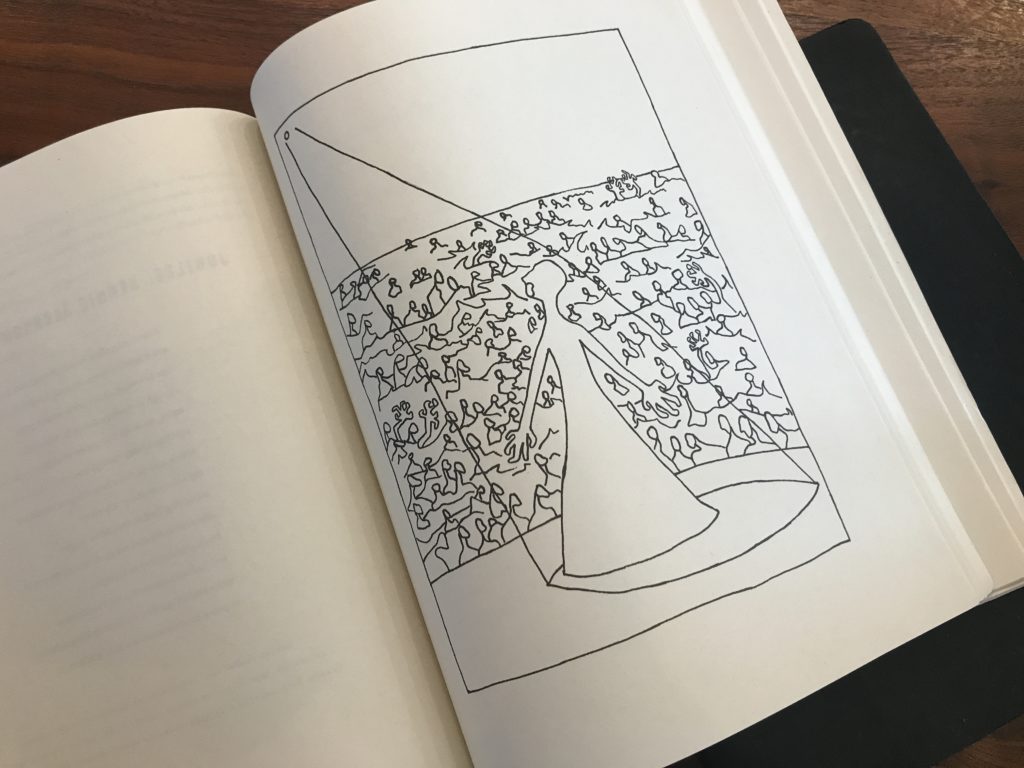

The weaving Jess encourages in the introduction is not only figurative but literal as well. The form of Olio literally expands in several different poems throughout the book—there are four fold-out pages that open up from the already large-size book. Each of these pages is perforated near the spine, leading brave readers (and those who pay attention to the appendix) to unfold, remove, and rebuild the poems in three-dimensional forms.

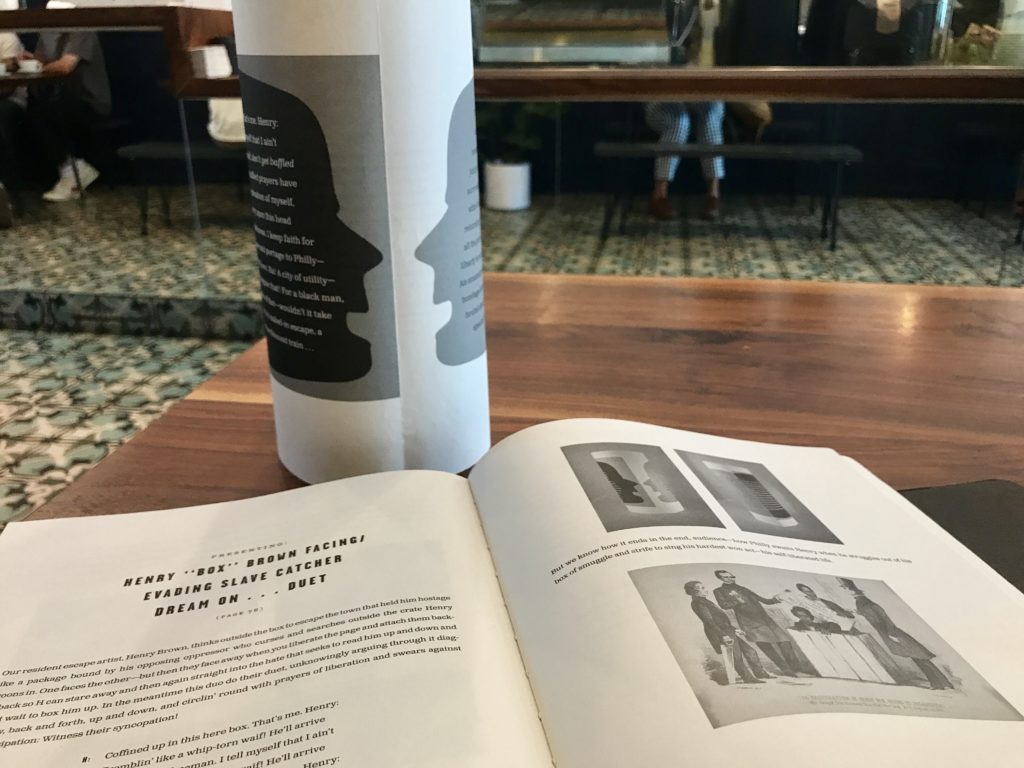

One of these fold-out poems takes on heightened significance as it gives voice to Henry “Box” Brown, a 19th century slave who mailed himself to the north in a crate to reach freedom. The page of the poem—”Freedsong: So Long! (Duet): Henry “Box” Brown facing/evading Slave Catcher”—demands to be removed by the reader in order to form a three-dimensional dialogue between Henry and the slave catcher. Brown, no longer confined to the flatness of the box, or the page, becomes the narrator of his own experience as he speaks directly to the slave catcher that opposes him. As the appendix demonstrates, Brown’s words alter the words of the slave catcher, giving authoritative power to Brown:

Brown: Coffined up in this here box. That’s me. Henry:

Slave Catcher: Tremblin’ like a whip-torn waif! He’ll arrive

B: Postage-paid freeman. I tell myself that I ain’t

SC: caught: sealed in slave chains again

This syncopated form reinvents Brown’s story for a contemporary audience who has often forgotten, if they ever knew, his story. As Brown “declare[s] salvation of himself,” he becomes the author of his own emancipation from “crammed darkness”—both within the confines of the box and of slavery. Jess’s Olio provides the third tier of that emancipation. With Brown’s story in the hands of the poet and the reader, they are witnesses and enablers of Brown’s literary emancipation—a long overdue emancipation that Jess affords to all his cast.

—Ashley Call

Share