The Double-Edged Impact of Literary Awards?

On March 31st, 2016, I attended a panel discussion at the Association of Writers & Writing Programs’ Los Angeles conference entitled “Literary Awards and Prizes: Help or Hindrance?” Moderated by Paul Morris, director of the literary awards for PEN American Center, the panel featured literary prizewinning poets and other members of the publishing world who are involved with artistic accolades. During the in-depth session the myriad benefits of literary honors were pinpointed, including the increased visibility, professional opportunities, and prestige that often come with literary prizes. In addition to an increase in authors’ bank account balances and the additional support from publishers that routinely accompanies awards, the panel members and moderator stressed that literary prizes provide an undeniable sense of external reinforcement by lending literary creators a reinvigorated sense of legitimacy.

Yet all panel participants equally argued that literary honors could be a double-edged sword, that along with the help they provide they can also create unintended hindrances. The sudden demand for selected books can overwhelm the publishing systems of small presses. It can be uncomfortable for winners to navigate the surreal and potentially awkward atmosphere of award ceremonies. For many writers, winning a literary prize represents a very public shift in their careers and professional communication for which they may be unprepared. For award winning authors of color, tokenization in the name of diversity can become a real threat to authentic expression and reception. But perhaps most importantly, literary awards can prove to be an actual danger to the act of writing itself. Panelists warned against the temptation to pander or laurel-rest, underscoring the importance of the continual quest for one’s best work.

Inspired by this complex conversation regarding the complications that literary prizes can bring, I thought it would be intriguing to communicate with past Tufts winners to determine the various impacts of Claremont Graduate University’s annual poetry awards.

Chase Twichell is the author of the arresting poetry collection Horses Where the Answers Should Have Been (Copper Canyon, 2010) and was the winner of the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award in 2011. For the past three years, she served as judge and chair for CGU’s Kingsley & Kate Tufts Awards. Brandon Som published his first poetry collection, the meditative The Tribute Horse, in 2014, for which he won the Kate Tufts Discovery prize in 2015. He earned his PhD recently from the University of Southern California’s Creative Writing and Literature program. Both poets agreed to ponder their experiences of being a Tufts winner and share the resulting observations.

When asked how being a Tufts Poetry Award recipient has positively impacted their lives, the authors each had a ready answer. For Twichell, being a Tufts winner provided her with increased recognition and allowed her the opportunity to pause her poetic flow. “The book that won the Kingsley Tufts Award was a new and selected [collection]…so it was a milestone for me,” Twichell reflected. “Okay – here’s what I’ve been doing for the last forty years. It could quite easily have passed through the world largely unnoticed, as so many wonderful new and selected [collections] do.” In addition to giving her a heightened sense of creative confidence, the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award allowed her “to close the door on that work. And it challenged me to take a vacation…I wasn’t ready to write new poems, so I spent about five months working on the yard and garden. Those hours were invaluable. My brain rested…I learned the value of downtime.” With her bright yet sardonic sense of humor, Twichell added, “Life will never be so good again!”

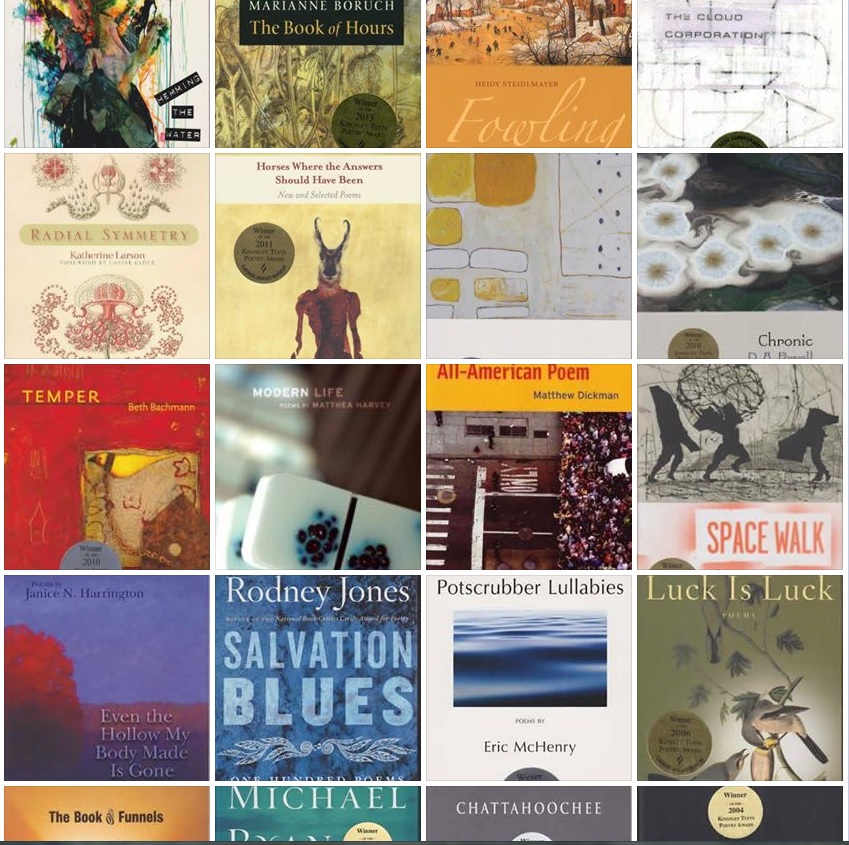

For Som, winning the Kate Tufts Poetry Award was an immense honor with definite positive outcomes including his inclusion into an elite group of awarded poets and an increased readership. “I have been reading and teaching [the works of] past winners of the award[s] for years, poets that include Yusef Komunyakaa, Marianne Boruch, Carl Phillips, D.A. Powell, Yona Harvey, Atsuro Riley, and Ross Gay,” Som explained. “These are writers whose writings have taught me so much. These are writers I look up to. For me, it’s a great honor to consider that my book of poems is in conversation with all the wonderful books that have been selected for…[these] prestigious prize[s].” The poet added, “The award has also placed the book in many more readers’ hands. For that, I am so thankful.”

When questioned if winning a literary award changed their perception of their own poetic process and output, Twichell and Som gave divergent answers. According to Twichell, winning the Kingsley award did not alter her artistic approach: “Absolutely not at all. I’d be worried if it had, because the poems I want to read and to write are the ones that are faithful only to themselves.” For this poet, the creative act is a sacrosanct and self-contained practice that should not be forced and she therefore does not feel tremendous pressure to produce for production’s sake: “As for output, I‘ve always been a slowpoke. If a poem comes fast it’s only because I’ve done all the hard work already, often without realizing it.”

Som indicated instead that for him being a Kate Tufts winner gave him a sense of renewed invigoration to create. “I’m not sure it’s changed my perception of my process, but it has given me support and encouragement to see my process through,” the poet responded. “Also, winning the Kate Tufts has given me a tremendous sense that my work on the page can reach others, that it has value and can even possibly effect change.” In regard to this intensified call to create, Som is delighted by the challenge of this increased sense of professional encouragement and impact as a poet: “I am extremely excited by that and grateful for it.”

In terms of artistic advice for aspiring future Tufts winners, each poet imparted important insights. Despite her modest claim that she doesn’t “know anything that past and future winners don’t already know,” Twichell offered sage words that can only come with experience and hindsight: “Prizes and awards come from outer space (and CGU), so our job is just to write the poems.” She continued, “I do worry about younger poets, for whom publishing, prizes, fellowships, etc. weigh so heavily in the search for teaching jobs. Winning an important award like the Kate Tufts instantly singles out a poet under consideration for a job.” But she insists that poets can only keep their creative attention squarely fixed on the act of creation alone, “No one can second guess the mysteries of who wins what, so as poets all we can do is continue to work, and be surprised and grateful when the world notices.”

Despite his comparatively shorter tenure as a published poet, Som also gave profound guidance for poets. “Central to the book [The Tribute Horse] and to my writing is the practice of listening – a practice that foregrounds the sounds of place and family, while finding inventive ways to listen to the past and memory,” the poet ruminated, “I like to point out for my writing students how the word memoir ends with the Spanish word to hear, oir.” Like Twichell, Som uniquely stresses the importance of writing for writing’s sake by insisting on turning deaf ears to peripheral concerns such as literary prizes; “My advice to writers is to place your ear to the past and present and focus on the resonances while at the same time turning up the volume on those voices that have been silenced or gone unheard.”

While the AWP panel initiated my interest in the ramifications of literary awards, my correspondence with these two Tufts poets helped me understand in greater depth the imperative need to privilege the act of writing over artistic honors. Though each poet’s prize-winning experience has been positive, it is important to note that Chase Twichell and Brandon Som, in their own idiosyncratic way, have made a conscious decision to dedicate themselves fully to their craft. Their unyielding focus has helped them to avoid the possible pitfalls of being an award winner while lending further strength to their verses. For each, creating poetry itself is the true honor. For this reason, both authors have managed to embrace the benefits of the Tufts prize without allowing any possibly associated interference to intrude upon their ongoing poetic efforts.

—Brock Rustin

Share