“Of Shadows and Mirrors”: Authoring Identity in Phillip B. Williams’ Thief in the Interior

“A reflection, a figment of a figment / of the imagination. The male figure stands / by himself, obscured” (“God as a Failed Figuration” 13).

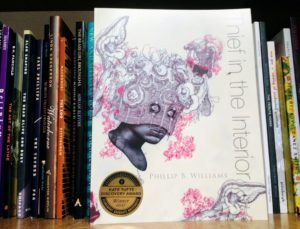

Phillip B. Williams‘ debut book of poetry Thief in the Interior has received a worthy amount of praise since its release last year. Winner of the 2017 Kate Tufts Discovery Award among other awards, it’s difficult to ignore the profundity in Williams’ poetic project as it incorporates elements of concrete poetry, devastating crime narratives, and an allusive playlist running through the collection with the likes of Miles Davis, Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, and Talib Kweli.

In the Los Angeles Review of Books last July, Rigoberto González read Williams along with two other books from emerging poets Derrick Austin (another Kate Tufts finalist) and Michael Prior. In this article González drew out the unmistakeable quality of intersectionality evident in all three of their works. These poets, González wrote, are “beginning their literary journeys with richly layered poetics that build from, and subsequently add to, our understanding of identity politics and intersectionality.”

There is little to contend with in González’s discussion of intersectionality present in Williams’ work. As he notes, the friction of identity politics is raised in an early question when the speaker of Williams’ first poem “Bound” asks, “Can I be only one thing / at once?” (1). To be sure, the intersection of black and queer male identity—in the United States specifically—is the center around which this book of poetry proceeds from (as evidenced quite literally in the concrete form of “Inheritance: Anthem” [14-19]). What’s more, Williams couples these questions of intersectionality with new and interesting questions of authoring an identity both as it is denied externally and as it is sought after internally. Who, after all, can author an “intersectional” self?

The fragmentary selfhood of the “male figure stand[ing] / by himself, obscured” (13) in Williams’ collection is represented throughout each and every one of the poems in Thief in the Interior. There is the boy who sees “an angel to call his own” in the shadow of the “Black Witch Moth” (2); there is the constant tension between light and darkness—light, as Williams says, doing “cruel thing to a boy’s face” (10); and there are the haunting and gruesome accounts of black male bodies violently disembodied (literally and figuratively) by what Williams calls “white writhing over black: the American aesthetic” (12). The voicelessness of these male figures, obscured in shadows and violated in light, is the place from which much of this poetry originates, even as the poems themselves seek to provide that voice.

But securing that voice is not the ordinary poetic project. As Williams shows in his section-length poem “Witness” (29), the honest narrative of the black, queer, male body is most often “Not Found” (40). In this chilling “true crime” poem, Williams inquires over the death of Rashawn Brazell whose face, he says, is remembered only in “the train’s face erasing the track beneath it” (39). As the poet attempts to “Tell the story,” he is also “Tell[ing] how a city phantoms a boy,” leaving no digital archive to speak of the murder: “all that’s recalled is dismembered” (38). And even in the speaker’s attempt to remember the boy, he finds erasure not merely of the boy in question but also of himself, “I called his name but heard my own” (31). (It should be noted that only very recently, post-publication of Williams’ book, they arrested the man who killed Rashawn Brazell twelve years after his death.)

In addressing the question of how one might author their own identity when confronted with an external world intent on not allowing that self-authorship, Williams expresses the deep fears of the obscured. The poem “Of Shadows and Mirrors” opens up the poet’s own strained relationship with his father, or what he calls a “a ghost” that floats “between [his] father’s ghost and [him]” (76). In the shadow of both his father and grandfather’s memory, Williams acknowledges that a mirror, or the act of self-recognition, is not always a simple remedy.

“My grandfather salted every threshold

to keep evil from entering his house. I heard

that salt stinging an open would means its cleaning

out demons, but maybe its crystal mirrors

are unwelcome, the body never wanting to see

its own inner ugly” (76).

You could never really exhaust the many layers of identity that Williams explores within Thief in the Interior, and perhaps that is the point. The concept of intersectionality, though so present in the abstract, is not so easily named when speaking about the real human, in life or in death. For this knowledge, or for a true representation of what intersectional identity might mean, we heed the words of poets like Williams who motion to us: “See my mouth move, like this—” (79).

—Ashley Call

Share